On Easter Monday 24th April, 1916, a group of some 1,000 Irishmen and women came into Dublin and occupied a series of buildings around the city. Their aim was to overthrow the British Government in Ireland by military force and to proclaim an Irish Republic. Over the next seven days, over 450 people died, 2,000 were wounded and the centre of Dublin largely destroyed by shelling. 15 of the leaders of the uprising were executed; a 16th was executed later that summer.

On Easter Monday 24th April, 1916, a group of some 1,000 Irishmen and women came into Dublin and occupied a series of buildings around the city. Their aim was to overthrow the British Government in Ireland by military force and to proclaim an Irish Republic. Over the next seven days, over 450 people died, 2,000 were wounded and the centre of Dublin largely destroyed by shelling. 15 of the leaders of the uprising were executed; a 16th was executed later that summer.

On the same day in April 1916, the second Battalion of the Royal Munster Fusiliers was stationed in France, awaiting orders for the next big push that was to become the Battle of the Somme later that summer.

There’s no real information about how soon the news of events in Dublin filtered through to Irish troops serving in France, or what impact it might have had on their mood. There are few reports of mutinies in the weeks that followed the Easter Rising; indeed the first that Irish soldiers may have been aware of the changed sentiment at home that followed the mass executions and internment was during their next leave home. Writers such as Sebastian Barry (in novels such as A Long Long Way) have vividly evoked that change in sentiment, as men who’d left Ireland as heroes returned to a hostile and embittered response.

Included in their numbers was my grandfather, Michael McCann, who had enlisted in the British Army in November 1915 and who had transferred to France some time in April 2016. It’s probable that he had been put to work as part of the Pioneer Battalion of the Munsters, providing the hard labour that created roads, tracks, emplacements and dugouts in the Loos-Marzingarbe-Les Brébas area (source Fourteeneighten Research). But by July he had been involved in the action that became the Battle of the Somme, one of the Great War’s bloodiest conflicts.

Afterwards, hundreds if not thousands of returning Irish soldiers left the British Army and joined the ranks of the Irish Republican Army where they became active in a campaign against a Crown that they’d been defending only months before. My grandfather was one such; he discharged from the British Army in March 1918 (he’d been treated for shrapnel injuries in 1917) but joined the IRA in England in October 1917, possibly having first joined an organisation such as the Irish Self Determination League or the Irish Labour Party. By 1919 he was on active duty with the IRA, taking part in arson attacks and munitions raids; by 1921 he was arrested during an attempted raid on an explosives magazine in Middlesbrough, and sentenced to five years penal servitude in Parkhurst. The subsequent Treaty and amnesty led to his release and return to Ireland in early 1922, just in time for the Civil War where he fought as a Free State Army commandant.

The Civil War had its own share of atrocities, but here too we’ll never know how battle-hardened veterans like my grandfather reacted to them. He kept it bottled up; even his own children knew little of his exploits, other than those reported on by a frequently partisan press. My aunts and uncles described him as a ‘quiet man’ who kept his thoughts to himself. Fragments of his story came down from my grandmother; over the last few years I’ve tried to research to fill the gaps. My collections Trapping a Ghost and Her Father’s Daughter (Salmon Poetry 2014) include some of the poems that resulted.

It’s clear that my grandfather was typical of a whole generation of Irishmen who experienced utter horror and were unable to find an outlet for those experiences. Irish society had embraced another mythology; the narrative of Irish nationalism left no space for other Irishmen who also believed they were fighting for their country.

One of the best elements of this current decade of commemoration has been the re-emergence of their stories. Works like Lia Mills’s marvellous novel, Fallen (which will be the Belfast-Dublin Two Cities One Book choice from April) are exploring the reality of lives for the thousands of individuals and families whose lives were transformed for ever, both by violence at home, and violence on those distant green fields.

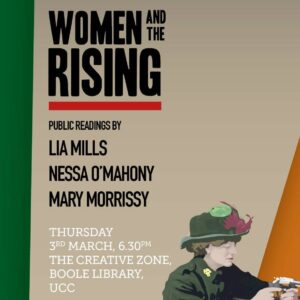

I’m incredibly lucky to be reading alongside Lia, and the marvellous Mary Morrissy, whose own novel The Rising of Bella Casey captured that tumultuous period of Irish history so well, as part of The Women and the Rising series at University College Cork on Thursday 3rd March. Further details on http://creativewritingucc.com/www/women-writers-remember-the-rising/.

I’ll also be leading a free creative writing workshop for the Open University on exploring family history at Castletown House in Celbridge, Co. Kildare, in late April. Details on how to book a place are on http://www.open.ac.uk/republic-of-ireland/events

4 Comments

Add comment Cancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

It’s interesting to look at what happened to the soldiers when they returned. My grandfather from the Shankill joined up at 15 in 1915, served to the end (wounded twice, dishonorable discharge as involved in mutiny!) , came back clearly with no trade and ended up an A special. And then from this experience became a communist in his 20s and was blacklisted from Harlands for his activities until WW2 needed him to build ships. As kids, we used to joke that he was the only member of the family who had been to the Continent!

That’s a fascinating story, John. He sounds quite a character. Have you written about him? That’s such an important story to tell.

Sadly my granny threw out all his papers when she left her house and my mother had dementia and couldn’t recall events I remembered hearing as a kid. You forget to ask more at the time.

Thank you!!1