Belinda Cooke reviews The Hollow Woman on the Island for issue 66 of The North

Nessa O’Mahony’s, The Hollow Woman on the Island is a beautifully rich collection from a mature poet, where the Grim Reaper’s ugly presence is compensated for with celebratory elegies for friends and relatives, as well as a highly nuanced journeying through her own cancer treatment. The contemporary relevance of the Easter Rising’s centenary is also very much in evidence. Throughout, her technically adept poems call on her readers – in E M Forster’s words – ‘only to connect’ as she juxtaposes physical and psychological states, both to share her intimate, sensuous engagement with the landscape, and make clear how Ireland’s tragic past still impacts on the present.

Thus, she opens: ‘Each decade found its own vortex / of imps straddling chests, white mares snorting’ (‘Bogeyman’) with seemingly disparate moments taking us from childhood to darker adult fears. Roger Casement’s reinterment in 1965 telescopes down to the cancer ward’s waiting room painted with an oh-so familiar shock of recognition: ‘a dead celebrity waving from the cover of an old Hello, / a raised bump beneath skin, a white-draped man / scanning penumbras on illuminated screens’. The temporospatial shifts in the 1916 reenactment of ‘O’Leary’s Grave’ is both playful and dark, noting how, ‘They’ll get it in higher definition / this time’, given the public’s initial disdain for the event, followed by a dig at de Valera’s less than glorious role during the week itself: ‘photoshop Dev in / if the direc- tor requires’, concluding with an echoing of Yeats’ ‘1913’:

‘Romantic Ireland’s dead and gone / it’s with O’Leary in the grave’ as a shift from 1916’s Irish Catholics to 2016’s Dublin drug addicts as the new dispossessed: ‘Zoom in to Romantic Ireland / blue-inked on his wrist’. She also takes us into the vexed issue of Irish World War One veterans who were at worst vilified and at best ignored,

Throughout, her technically adept poems call on her readers – in E M Forster’s words –

‘only to connect’ as she juxtaposes physical and psychological states ...

delicately touched upon by juxtaposing her visit to the 1916’s leader Pádraig Pearse’s old experimental school of St Enda’s with her mother’s one to the French war grave of a relative who died in the final months of the war: ‘We shall not forget, how could we? / Shared genes give the same nose, / domed head, the pale blue eyes

...’ (‘Age Shall Not Weary Them’).

She draws on her meticulous passion for landscape

and wildlife to celebrate and lament. Ireland’s tragic past – its famine, poverty, repression, stagnation and necessary emigration – haunts the collection. Unmarked graves are the living reminder of all that past as in this lovely spare poem taking us into the bleakness of that blank terrain:

The grass grows the same here: the odd blown-in

pollinated by cloven hooves. We keep our mouths shut, look the other way

(‘Folk Memory’)

The land is also remote and unforgiving: ‘... memories of going Winter-mad // ... Black dog, black moods, black God’ (‘“In Ainm Croim”’), yet also a source of simple pleasure as we see her debunking the recent emphasis on STEM subjects by noting the poetry within science:

‘Dreamers gave us mother of pearl / and you know what trouble / dreams got us into’ (‘From a Beachcomber’s Manual’). Certainly she, herself, observes that natural world with the scientist’s eye, along with environmen- tal concerns: ‘like the names of things / we knew only yesterday’ (‘Absence’); her microscopic observation, ‘one downpour / would tear those skirts / trample the soil / with petals’ (‘A Poppy for Aiofe’), always the patient nature watcher: ‘I stand and watch droplets lined up as if waiting for something ... They outstare the watcher: I move on’ (‘April Hawthorn’).

And all the while, death walks the collection. Elegies come thick and fast: ‘we’ve stalked death’, ‘Another bell: / and I know / for whom it tolled, old friend’ (‘Do not Ask’) along with her sequence on her own brush

with cancer. Here, with its mild echoes of Plath’s water imagery in ‘Tulips’ (Ariel) – she really blows us away with an extended stone and water metaphor (the gravestone reference, perhaps, a step too far) to unpick the impact of a life-threatening illness versus writing as a gift against that dark:

Edges rounded off

by the water’s oscillation

till she’s smooth, buffed

into ovoid shape,

tide-tossed onto damp sand, to be plucked up,

pocketed, placed with care on a mantle-piece, a grave-top.

(‘The Hollow Woman on the Island’)

Trace your truth

with a thumb, a tongue, an index finger,

a thought,

a scratch on paper.

(‘The Hollow Woman at Bohea’)

Be gone 2020, I would not have you back

We are nearing the end of year that nobody will miss, although there have been sterling efforts to find the silver linings in it. I have endless admiration for those who managed to clear their head of all the chaos and panic and distractions engendered by the pandemic, and who were able to plough on with their creative projects, or even dream up new ones.

I regret that I wasn't one of that body. From the first news update, I've been lost in a perpetual cycle of checking feeds, counting numbers, becoming obsessed with world events that I have no personal interest in, or control over. I tried to write - but found inspiration hard to come by. It became even harder to come by when I was awarded a small grant by the Arts Council to respond to the pandemic, and after an initial spasm of creativity, my ideas dried up to a small knee jerk. I changed tack and tried to restart my novel - surely in the downtime afforded by lock-down, I'd be able to do that at least. But that well was dry too.

The one time I felt the remotest connection with my creative self was during a two week holiday in Co. Kerry in August, where I was able to sit and watch the mountains and sea and felt safe. The daily rhythms of walks and eating and sitting and watching were all that was required, apparently. But once I returned to the cell of four walls, little sky and concrete pavements, the paralysis resumed.

So I'm hoping that 2021 will be a better one for this writer, anyway. That the anxiety will reduce as the good news spreads and people feel safer. And I hope that the bookshops can stay open, and that publishers can resume their launches and that all the writers whose books came out this year will get lots of attention and airspace next year. I hope that 2021 will be a better one for my loved ones and for those friends who I'd love to have a casual coffee with some time again. I hope that my courage will return, and with it, the glimpses of pattern and shape that I've missed so much.

Things for which there is no longer purpose

It takes time to get your eye in, when beach combing.

Stones merge, little distinguishes itself from shingle,

pell-mell debris of tides on the channel

between this side and the next.

You need to keep your glance down,

let the slow rhythm of step after step,

pebble after rock after pebble,

give distinction, let shapes emerge

and form into sea-glass, shells,

gaping crabs, innards violet.

The urge grows to find patterns beyond

the Fibonacci cockles.

Why this search for meaning?

What can this nibbled lid of a ceramic coffee pot

tell me of accident, of transience?

Or this, a knuckle of sandstone:

sea-tossed, hand-crafted, who knows?

Or, most mysterious, the metal-encased,

rust-imbued pipe. Ship’s screw, gas line,

fifty years, two centuries, tossed by waves,

then dumped without ceremony?

Who says its purpose was to be found,

to be understood?

Earlier, we turned hair-pin bends

in search of beauty.

There was a time when I could navigate,

feel the grip of wheel, trust my steering,

my courage.

Now I leave that to you,

knowing that more than coins flip,

that every breath has two outcomes.

Valentia Island, August 2020

Billy Mills reviews The Hollow Woman on the Island

(from Elliptical Movements May 2020 - https://ellipticalmovements.wordpress.com/

Nessa O’Mahony’s most recent book is determinedly Irish in conception and construction, drawing as it does on figures and events from Irish history, particularly the early 20th century and the period of the Troubles and highlighting the intersections of family and national history and geography and the influence of religion on both. The influence of Irish poets of the canon, especially Yeats, Kavanagh, Heaney, Mahon, Kinsella and Boland, is also evident in the writing.

Unlikely looking gift, this five-barred

metal gate, rusting, crossed,

tethered in its lock by blue nylon strings.

The signs unwelcoming: dogs beware,

walkers climb at their peril

in this kingdom of scrub and rock.

O’Mahony is a very literate writer who uses the tropes of the tradition with considerable skill, extending them by the inclusion of female experience that has often been marginalised. This is particularly the case in the fine sequence of poems that give the collection its title. This set of four Hollow Woman poems deal with the poet’s experience of ovarian cancer in an idiom that seems to owe much to middle-period Kinsella, an idiom that O’Mahony does much to make her own.

What matter

if the eye of faith betrays?

Trace your truth

with a thumb, a tongue,

an index finger,

a thought

a scratch

on paper.

Ultimately, however, this writing is best read as an extension of the tradition, not an expansion of it. It is poetry that is comfortable within its clearly defined limits.

The question arises .... whether or not poetry written out of a supposed shared unproblematic sense of self which is in itself problematic do justice to the world we inhabit? On the whole, and not, I think, unrepresentatively of most contemporary verse, the voices we hear reflect a Wordsworthian ‘man speaking to men’, more inclusive, admittedly, not narrowly gendered, but still fundamentally wedded to the basic assumptions of the ‘Preface to the Lyrical Ballads’ and its associated Romantic sensibilities and expectations. ... Which is not to take from the undoubted skill of the other poets under review; they all do what it is they set out to do with a great deal of ability, but it would be interesting to see them take more formal risk in their writing, to expand the idea of what poetry is, and is for.

Fred Johnston reviews The Hollow Woman on the Island

Whoever penned the jacket blurb unfortunately employed Pentagon-speak with the phrase 'existential threat' to describe O'Mahony's latest collection. I've never been sure what the phrase means, politically or otherwise. The threat here arises from O'Mahony's brush with ovarian cancer and how this experience raised questions about womanhood and 'female identity'. I suppose for those of us who've had prostate cancer, similar male issues ought arise. Do they? Perhaps not quite to the same extent. But one must concede that the 'hollow woman' of the title might diagnose a psychological point of view relevant to women, which men do not experience.

Unsurprisingly, the second section, which treats of the medical experience, reflects some of what I tackle in my own collection, Rogue States. I do not mention my collection gratuitously, but to emphasise the conditional unity of such experiences. Images of imprisonment, a cell-like mental environment, couple with the 'prisoner's' fear of a door opening to admit a torturer. This is the nature of illness - to trap, to intimidate, to hint at further misfortune. In such a condition, language assumes sinister import; terms once foreign become familiar. The word 'rogue' creeps in, not as in 'loveable rogue' but the rogue of treacherous cells. O'Mahony manages to capture in four poems a world of personal metamorphoses. Outside of these, she utilises the language of woman-ness in resonant and often startling ways.

For my money she - with her precise and musical sense of language and her concern to, well, get it right - is one of our better poets. I think it is fair to say that her vigilance interrogates subjects that are genderless and equal. Oh that more male poets would, or could, speak honestly of their vulnerabilities.

(Fred Johnsont, In: Verse, Books Ireland, November/December 2019)

First review for The Hollow Woman

Many thanks to John McAuliffe and the Irish Times for including my latest poetry collection, The Hollow Woman on the Island, in the latest reviews round-up. Here's the link and text:

New works by Nessa O’Mahony, Catherine Phil MacCarthy and Patrick Deeley

Nessa O’Mahony: her work has a confident grasp on family and inheritance. Photograph: Frank Miller

Creation and inheritance are at the heart of Nessa O’Mahony’s The Hollow Woman on the Island (Salmon, €12). Although O’Mahony’s style generally aspires to plainspokenness, the book includes a pattern poem or calligram, Simple Arithmetic of the Human Egg, which takes the shape of an egg and counts down from human generations, “Born/with two/ million but the/ maths are insane,” to the different matter of artistic creation, “pebbles washed up,/ edge wavepolished/ into Henry/ Moore.”

The central, title sequence recounts the experience of ovarian cancer – “The soon to be hollow woman waits/ in a room with four doors, all closed”, documenting recognisable scenes (“She looks at the piles of glossies/ from two years ago and picks one up;/old news is better/ than new news”) but still protectively noticing the outside world, “two parent wrens / cordoning a fledge / as it careered / from hedge to vine / and back again, / settling on the slant / of the garden shed.”

O’Mahony’s strongest poems are those in which her confident grasp on family and inheritance are placed in relation to an object and image (like that “wavepolished pebble”) which sets her world in relation to something else, a new idea or frame of reference. The book remember neighbours, a watchful “Mrs Pass If You Can”, and north Cork relatives, while a memorable elegy, The Hare on the Chest, makes “the zigzag chase of a breathless hare” become its subject’s resting place. The book’s more occasional poems lack such specific images and forceful metaphors as they recount debates about Stem, or encounters with Joyce, poetry at UCD or Mary Wollstonecraft.

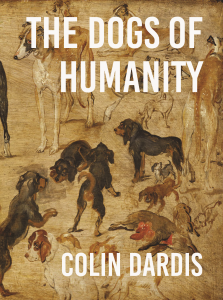

Guest post by poet Colin Dardis on poetry and mental health

To coincide with the launch of his latest poetry collection, 'The Dogs of Humanity', I'm hosting poet Colin Dardis, who discusses here the overlaps between poetry and mental health in his work:

“I have not been named,

so they never talk of me. I call myself runt,

a title earnt through exclusion.”

(‘Runt’)

I’m twelve, and sitting in my doctor’s GP clinic, waiting to be seen by a nurse for an appointment. The reason why I am here exactly have been lost through the distance of time. However, a new reason for future appointments will soon appear.

I’m on a cushioned bench, on my own, outside the nurse’s office. The colours are all pastel blue and light grey, simple neutral tones you’ll find in any surgery. Suddenly, I’m overwhelmed by a pounding headache, a sense of dizziness… I feel like monsters are rushing at my from off the walls, creatures I can’t really see but it feels like a video game where you can’t shoot fast enough. I close my eyes and lower my head. The sensation lasts a minute and then passes. I don’t know what to make of it, and do not mention it to anyone.

Years later, I came to realise that this was my first panic attack. And since then, I’ve been struggling with depression and anxiety all throughout my adolescence and adult life.

“How many are scared tonight?

How many want to burrow into the nest

like the newly-hatched cuckoo

and cry the loudest in order to fed…”

(‘The Humane Animal’)

Of course, I didn’t realise this at the time. In my teens, I didn’t identify as someone with depression, didn’t seek a diagnosis, or given any medication or therapy. Twenty years ago, there just wasn’t the awareness we have now of these issues. So instead of talking openly about these issues, knowing I was somehow different from ‘the norm’, everything went into poetry instead.

Writing allows a realm in which to explore and try to understand the things that didn’t make sense in everyday life. How do people relate to each other? How is one supposed to behave? What am I expected to do with my feelings? Life rarely gave answers to these questions, but in poetry, you could create your own makeshift answers. Or at least, the question seems less daunting than before.

A lot of poetry in the past has been introspective, as mental health was my main impetus to write. However, as I’m grown older (not necessarily matured!), and grown more comfortable in sharing my experiences, I’ve realised that more and more people are experiencing something similar to me. That at times they have felt lost, unsure of the future, burdened with a grief they can’t quite explain. And so my poetry has moved to try and look at that bigger question of the human condition, to advocate for more empathy from people, to dig into a place of resilience. In a society where we say “it’s okay not to be okay”, there are still so many people unable to speak up. Poetry, whether in the act of writing or reading it, gives us the opportunity to find those words unsaid, to perhaps find a little comfort through words, which ultimately, can lead to actions.

“Life would not reach print

by the high demands

of us human publishers,

yet it is the only manual

we have to read.”

(‘Unpublished’)

Colin’s new collection, ‘The Dogs of Humanity’, is out 1st August, available to pre-order now from Fly On The Wall Press:

Print: https://www.flyonthewallpoetry.co.uk/product-page/pre-order-the-dogs-of-humanity-by-colin-dardis

Kindle: https://www.amazon.co.uk/Dogs-Humanity-Chapbook-Colin-Dardis-ebook/dp/B07TCBCZ64/ref=sr_1_3

Launching a new poetry collection - The Hollow Woman on the Island

We had great fun launching my fifth poetry collection, The Hollow Woman on the Island, at Poetry Ireland on 28th May. I was in excellent company, as Jo Slade and John Murphy were also launching new volumes with Salmon Poetry, our publisher. I was also incredibly lucky to have the amazing Katie Donovan as my 'launcher' - here's her very generous comment on my new book, which can be ordered online from Salmon's website at https://www.salmonpoetry.com/details.php?ID=509&a=281

"Themes of family, mortality, faith and art inform this new collection from Nessa O’Mahony. Although the title, The Hollow Woman on the Island, suggests loss and limbo, the book rings with birdsong, the fluting of an old gate in the wind, family anecdotes from Cork to Vienna, and concludes: “prayer starts in the same place as story”.

Many years ago, Nessa’s bright enthusiastic face and incisive comments lit up my Creative Writing class in the IWC. Her consistent output ever since – from four volumes of poetry to her novel, The Branchman, and her work as an editor of two anthologies - has brought her to the centre of the writing scene in Ireland and abroad. This is her fifth collection of poetry – another book to be proud of. And may I say, as her former “teacher”, how proud I am as well.

There are several powerful poems in The Hollow Woman on the Island that give voice to a fear so many of us have known, as doctors hover with scalpels and jargon, offering “butcher’s cuts of possibility”.

The unbearable, post-surgery lightness which, for a woman who has lost her fertility, is so cruelly ironic in its ovoid shape, is expressed beautifully and heart-wrenchingly in the title poem. A similar delicate approach is evident in “Alcmene’s Dream”, which ends with an absent cradle, and first appeared in Metamorphic, the anthology of poetic responses to Ovid which Nessa co-edited in 2017.

With the beautiful poem in celebration of her niece’s wedding, Nessa brings this theme to bear on the larger picture of a family and its collective fertility – the significance of the role of each member within that circle.

Nessa’s well-known gravitational pull towards history is evident in many of the poems, one of the most eloquent being “O’Leary’s Grave” where some of Ireland’s shamefully large population of homeless citizens bed down in Croppies Acre while a scene is shot for a movie about The 1916 Rising.

Her capacity to depict landscape with the deft shapes and colours of a painter’s eye is also in evidence, from the Bohea Stone in Mayo to Cill Rialaig in Co Kerry, and our own local river, the Dodder. Wildlife abounds, from fledgling wrens to otters and hares.

Wisdom, lightness of touch, vulnerability, craft and ironic flourishes. Family, travel, friendship and political awareness. There is much to mine in this new work.

Finally, I like how she chooses to end the collection, with a vision of Homer as a woman. For we know that Homer represents a collective circle of narrators, within a large family of storytellers, each with a vital contribution to make to the endeavour as a whole."

Katie Donovan, at Poetry Ireland, 28th May 2019.

Discussing the creative response to historical events in early 20th century Ireland

I recently gave a paper at the inaugural Association of Writing Programmes Ireland conference at University College Dublin about the challenges of writing historical fiction - I was part of a panel with novelist Mary O'Donnell, who discussed the writing of her recent short fiction collection, Empire (Arlen House 2018). There was some fascinating discussion afterwards so I'm posting my paper here:

FINDING THE FICTIVE SPACE WITHIN CONTESTED FACT

As our abstract has suggested, the current Decade of Commemoration has brought into the open many stories previously hidden from the narrative mainstream of received history. In my presentation I am focussing on the creative response to the convulsive events of the first quarter of the 20th century, namely World War I, the Rising and War of Independence and Civil War, using my own experiences as a creative writer as the main basis of discussion, and seeking to place that practice in the tradition of how others have responded imaginatively to the period.

In this presentation, I’ll consider the issues around the creative response to factual events in the first quarter of the 20th century, before focussing on my own experience of writing the first novel in a trilogy exploring the experiences of an ex-army turned policeman in the Irish Free State. When I began this paper, I had a fairly clear outline of what I intended to cover. But that was before the events in Derry last week when journalist and writer Lyra McKee was shot dead during rioting in the Creggan, when a paramilitary took aim at police and killed her instead. That event reminded me that politically-inspired violence in Ireland is not confined to history, and that writers continue to have to grapple with the legacy of our confused and contested past. I’ll return to that point at the end of this paper.

Understanding the past is crucial, and when you begin to write historical fiction, you quickly realise the limits to your knowledge of history. I was speaking to another writer recently about how we were taught the subject. She, a generation ahead of me, mentioned that secondary school history had stopped at the Tudors. In a brief addendum, the 1916 Rising was mentioned as having taken place, but no future details were provided. This was in the 1960s, when the events at the GPO and elsewhere were not even half a century old. I studied history at school in the 1970s, and took it as a subject at university here in Belfield in the early 80s. By that stage, there were plenty of accounts of the Easter Rising, and whole text books consisted of a chronology of rebellions from the Flight of the Earls to Soloheadbeg, that suggested the only possible relationship between Ireland and England was a dysfunctional one, with uprisings the inevitable and sole solution. This kind of history focussed on the minority of men and women involved in the planning of those uprisings; little account was taken of the majority of the population whose lives were of course affected by political events but who went on with their day to day routines as best they could – the one exception were the lectures of Mary Daly, who crucially conveyed the social history in an admirably compelling way. But, by and large, the stories of everyday men and women of the period remained untold.

By the historians, that is.

Writers were a different matter, and although literature of the political unrest was not numerous during the early decades of the 20th century, there were notable exceptions. Yeats, of course, gave us his own idiosyncratic take on violent nationalism. Sean O’Casey’s plays represented ordinary men and women caught up in extraordinary events. Juno and the Paycock tackled the harsh brutalities of life during the Civil War – his Shadow of a Gunman attracted enormous contemporary criticism for its unvarnished depiction of both revolutionaries and Dubliners. Liam O’Flaherty’s The Informer, published in 1925, won the James Tait Black Memoiral Prize that year for his depiction of Gypo Nolan, the eponymous informer who goes on the run in the Civil War. In 1929, Elizabeth Bowen published The Last September, which told the story of the Anglo-Irish family The Naylors against a backdrop of the War of Independence. In 1931, Frank O’Connor published his short story “Guests of the Nation,” in a collection of the same name. For many years this was considered the seminal story of the War of Independence, telling as it did the story of two British soldiers shot dead by the Irish Volunteers during the War of Independence. It was certainly the only story dealing with the period that was on the curriculum when I was at school.

But in the 30s, it seemed to go silent. Scholars will have their theories about why the period between 1930 and 1970 did not produce more writing about the bloody events that had given birth to the Irish Free State and then Republic. De Valera’s Ireland did not encourage much self-reflection or social scrutiny so writers may have preferred to cast their nets elsewhere – one thinks of the surreal satire of Flann O’Brien, or the medieval monastic whimsy of Mervyn Wall’s Unfortunate Fursey.

It’s certainly possible that the Censorship Board, established in 1929, might also have had something to do with. Although its remit was the safeguarding of ‘public morality’ through the banning of obscene literature, it soon became clear that the Censor took a very broad view of what constituted ‘obscene’ and soon was banning anything that might challenge a very narrow public consensus. In such a climate, it was hardly likely that Irish writers would seek to challenge political orthodoxies.

And so it remained until the mid-60s, when the social climate began to change and slowly, gradually, people began to challenge nationalist pieties in a way that would have been unthinkable previously. The historians may have started writers rethinking their approach – when I studied history here at UCD in the early 1980s, revisionism was only beginning to make itself felt, and early work by Ruth Dudley Edwards, amongst others, began to suggest that we might find other ways of looking at long-held truths, though that was not the consensus view by any means. Creative writers may have been emboldened by that revision.

But it was an uncomfortable time to be doing so. The Northern Ireland Troubles were under way, and from my very youthful perspective at the time, it felt like there were divided loyalties in the Republic. We still liked to cheer whenever the British got beaten in any sport, but, depending on your viewpoint, honouring our Fenian Dead could be seen as acknowledging a link between them and the current breed of paramilitaries responsible for such carnage on both islands. How to reconcile that sort of cultural ambivalence, and how to write about it creatively?

I don’t have the scope in this paper to discuss the literature of the Northern Irish Troubles. Given that my own creative focus has been on the first quarter of the 20th century, since I began to explore in fiction the lives of the men and women caught up in the various conflicts of that period, that’s what I want to discuss now.

Julian Gough once courted controversy by stating that Irish novelists were obsessed with the past. Writing in his blog in 2010, he said: The older, more sophisticated Irish writers that want to be Nabokov give me the yellow squirts and a scaldy hole. If there is a movement in Ireland, it is backwards. Novel after novel set in the nineteen seventies, sixties, fifties. Reading award-winning Irish literary fiction, you wouldn't know television had been invented. Indeed, they seem apologetic about acknowledging electricity.” (https://www.theguardian.com/books/2010/feb/11/julian-gough-irish-novlists-priestly-caste accessed 18/4/19)

Gough rowed back on his comments a little later, but it’s interesting to consider, even in his commentary, the lack of focus on the earlier part of the 20th century. Where were the contemporary novelists who were writing about that period (Apart from Jennifer Johnston’s How Many Miles to Babylon, published in 1974 and still one of the finest Irish novels about the Great War)?

The decade of commemoration acted as a galvanising force, it would seem. Two things were going on here. Firstly, the more the public discourse turned to considering and reconsidering the events of 100 years ago, the more writers began to explore that world imaginatively. Secondly, I’m sure there was a commercial imperative. Publishers are quick to see the attractions of anniversary-themed books (think how many books came out this year around the theme of female suffrage and forgotten women) so they may have been more open to proposals around historic themes. It can be no coincidence that over the past two decades we’ve seen books by Roddy Doyle (His The Last Roundup Trilogy which began with A Star Called Henry, 1999), Lia Mills (Fallen), Sebastian Barry (A Long, Long Way), Mary Morrissy (The Rising of Bella Casey) and, in the crime/thriller field, series by Kevin McCarthy and Joe Joyce among others. Nicola Pierce and Sheena Wilkinson have been exploring the period for children and young adult fiction.

For me as a poet and novelist, it seemed inevitable that I would be drawn to the period. I grew up hearing about the adventures of men and women in that period of time. My mother is a terrific storyteller and my childhood was filled with accounts of my grandfather’s exploits in the War of Independence, and the Civil War. When I began to write, I quickly found that family history was an important subject matter for me. But there were gaps in my knowledge. Family history is never complete, particularly when reticence is part of the mix.

It was only when I began, five years ago, to professionally research the life of my grandfather, Michael McCann, that I discovered that there was considerably more to him than family history had told. Not surprisingly, those family stories had centred on his role as a Volunteer during the War of Independence, though details were sketchy even there, and as a Commandant in the Free State Army during the Civil War. There was practically no mention of the fact that he’d fought on the Somme in World War I – that part of his backstory had been carefully elided. But as we approached the centenary of the start of the First World War, I was anxious to fill in the gaps and, with the help of my surviving uncle, Liam McCann, who was in possession of Granddad’s soldier’s pocketbook, which gave his medal number, I was able to track down a fuller account of his involvement. He enlisted in 1915, joined the Royal Munster Fusiliers, and spent 1916 and part of 1917 on the Western Front, in particular the Somme. He was injured by shrapnel, and invalided out in late 1917. It was then that he moved to North East England, and joined a faction of the Irish Volunteers.

I had written about his Civil War activities in my second poetry collection (Trapping a Ghost, bluechrome 2005), but I’d never written about his First World War activities. Now, with the additional information I’d gained through research, I was able to write a series of poems that charted his progress through the war, and the legacy of injury it had left. Those poems appeared in my 2014 collection, Her Father’s Daughter; I used as the cover photo a snap of my grandfather in his Royal Munster Fusilier’s uniform. I’d not been aware of the photograph’s existence, nor had my mother, but was sent it by a second cousin I uncovered during online research into my grandfather’s family. On the night of the launch, I discovered that choice was not entirely uncontroversial. At the end of the evening, an aunt approached me, wondering why I hadn’t, instead, used one of the many photographs of Granddad in his Free State Army uniform. The family was not universally ready to accept the many-faceted nature of my grandfather’s history, it would seem.

And yet, that was precisely the point of writing those poems, and making use of that photo. My grandfather had not spoken at all about his First World War record, in common with the thousands of Irishmen and women who’d survived that bloody conflict, and who had come home to an Ireland ‘changed utterly’ and utterly unreceptive to their plight. If they did talk about it, they could be a target for political nationalists. So the safest thing to do was to stay quiet. I was convinced of the need to to reinstitute at least one of those voices, to claim that covert experience fighting for Britain as every bit as valid and worthy of writing about as the more politically acceptable activities that followed it.

The choice of my next book, a crime novel inspired by my grandfather’s 20-year career in An Garda Siochána, seemed a less controversial choice. There was more family anecdotal evidence to draw upon, as my mother and her siblings were around for most of it, but there were still gaps in their knowledge, stories half-remembered or conflated. And when I approached the Garda Archive in Dublin Castle to see if they had further information, they sent by return of email an A4 document that provided the bare minimum: his badge number, date of birth, date of appointment (28 March 1925), the stations and divisions where he served, monetary awards received (for good police duty) and date of discharge (29 March 1945). Oh, and the final entry, was a description of his total service as ‘Exemplary’. That could have covered a multitude.

As you know, there’s nothing a writer likes more than a vacuum, because that’s what frees up the imagination and allows us to invent. I became convinced that if officialdom couldn’t give me the facts, some imagination backed up by historical research might help fill in the gaps. The more I read of the background, from local newspaper reports and historical accounts, the more it became clear that the new police force Michael McCann joined had been thrown into the deep-end of an Irish society still deeply divided and lawless after the ending of the Civil War. It was a society I was deeply curious about, but one that I had rarely if ever read about. Thus it was one I wanted explore in fiction.

The background to the Special Branch that my Grandfather joined, and which is the subject of my novel, The Branchman, is as follows. In the period immediately after the end of the Civil War, Minister for Home Affairs Kevin O’Higgins and Garda Commissioner Eoin O’Duffy decided that a restructuring of the police force would be required to provide the sort of policing needed in a still highly unstable situation. So in 1925, the Garda Síochána and the Dublin Metropolitan Police were amalgamated and, as part of this newly unified body, a new entity was created, the ‘Special Branch’. The leader of this new outfit was to be David Neligan, one of Michael Collins’s original secret service agents and now a Colonel in the Free State Army.

My grandfather, Michael McCann, was appointed as a member of the Garda Síochána of 28th March, 1925, and joined the Special Branch on its formation shortly afterwards. He was stationed first in Letterkenny, before being moved to Ballinasloe in 1929, where he spent the majority of his career.

My fictional hero, Michael Mackey, was also appointed to the Special Branch in 1925, although he went straight to Ballinasloe to conduct his investigations into suspected subversives in the area. Although the plot is highly fictionalized, I did draw on actual events. For example, I’d read an article in the Irish Times archives that cached ammunition left over from the Civil War regularly caused security problems in small Irish towns. For example, 1st March, 1930, there was a major blast at the back of Society Street in Ballinasloe, which led to the demolition of some shop fronts and the destruction of the offices of the local newspaper, The East Galway Democrat. As The Irish Times reported, “investigations were made by the Civic Guards, and it is thought that a land mine, which was probably hidden by someone who wanted to get rid of it in an ash pit or somewhere behind Society Street, was accidentally exploded”. I took the kernel of this event for the novel, and an early incident involves Mackey discovering a cache of weapons in the murder victim’s coal shed, and engaging in a shoot-out with one of the subversives.

Another plot twist inspired by actual events came courtesy of my uncle, Liam McCann (now dead), who also remembered an event from the early 1930s. There had been a hurling match in Duggan Park in Ballinasloe. It got out of hand and my grandfather arrested a man and brought him down to the barracks. A mob came down to try and storm the barracks and Granddad had to fire a gun over their heads to disperse the crowd. In the novel, this gets translated into a major grudge match between two arch rival teams in a county final that occurs on the same day as a visit to Ballinasloe by Minister Kevin O’Higgins. The fans have been infiltrated by subversives who incite a riot that spills out into the official visit, with fatal consequences.

By the way, I am only too aware that my choice of terminology – of subversives and Irregulars – might seem to nail my political allegiances to the mast. The Free State authorities coined the phrase ‘Irregular’ for those men who were against the Treaty and formed their own military opposition to it. Those who grew up in that Anti-Treaty tradition would more likely refer to them as Volunteers, or Republicans, phrases that are as loaded today as they were then – the initial statement commenting on Lyra McKee’s death was attributed to Volunteers. But although my protagonist Michael Mackey might be in no doubt about who the ‘baddies’ were in 1925, the reader will gradually discover that things in the new Free State are not quite that black and white. People on all sides of the divide are forced to compromise morals and integrity on a regular basis; my choice of the crime genre provided me with a useful framework for such an exploration. Crime readers are used to depictions of corrupt societies where nobody is beyond suspicion; my use of a small Irish town as a microcosm for larger dark forces at play in a riven Irish society would not shock anybody familiar with those tropes. Indeed, a recent review of the book by novelist Pauline Hall recognized those similarities:

"The originality of this novel lies in O’Mahony’s treating of dirty work in Co Galway in 1925 within many of the conventions of American private eye fiction. I suspect that Nessa is, like myself, a fan of the peerless Raymond Chandler. Her hero, Michael Mackey – the Branchman – has to go down mean streets, without being mean himself. Like Philip Marlowe, he can exchange blows and shots when required, but he resembles Marlowe also in his stubborn principles and his romantic attachment to a tough broad."

But does writing in a recognizable tradition such as the crime thriller allow one license to mix fact and fiction in such a way? I would argue yes, although I’m aware that more than one reader (with connections to the town) has complained about the depiction of Ballinasloe people in the novel, although others had no such problem. I’d claim that novelists must engage with the past through their own imaginative filter. My protagonist bears more than a passing resemblance to my grandfather but, as with many fictional heroes, has his own characteristics, flaws and plot points, which almost certainly never happened in real life, or at least not in the way I tell them in the novel. But isn’t that is the joy of historical fiction; it presents an alternative reality. If the writer can make the reader believe in that reality, at least from the first page to the last, she has succeeded in her task.

Or so I thought before the events of last week in Derry City. Now I wonder whether writers have a duty to the past, to recognize that what might be considered finished business in some eyes is still very much alive and current and thus must be handled with greater care and attention. Might that explain the silence that descended upon Irish writers in the decades after the cessation of the Civil War, a reluctance to deal with what was very much still a source of live debate and dissention? Was it the ending of the Northern Irish Troubles in 1997 that freed up creative writers to tackle these subjects again? And will the arrival onto the scene of a new generation of paramilitaries still trying, in the words of Paul Brady, to ‘carve tomorrow from a tombstone?’ make us more hesitant to write about those events of 100 years ago?

I don’t have any answers to this. I know that as this decade of commemoration advances, more and more stories will be unearthed about the unstable society that the new Free State attempted to pacify in the aftermath of Civil War. It remains a rich subject for fiction; I hope I hold my courage to continue that imaginative exploration.

Thank you

Mayo's Marlowe: The Branchman reviewed in Dublin Review of Books

A Marlowe from Mayo

The Branchman, by Nessa O’Mahony, Arlen House, 362 pp, £26.95, ISBN: 978-1851321896

In her new novel, The Branchman, Nessa O’Mahony turns to recent Irish history with a fast- moving yarn set in the jittery period shortly after the Civil War. It is an inventive touch to focus on the Civic Guards, whose title echoes the recent troubles. In the town of Ballinasloe, as throughout Ireland, the Garda Síochána are an important group. They stand in many ways at the forefront of efforts to calm and normalise life for a society still traumatised. Yet they too ‑ as individuals and as a force – are divided and damaged. As Superintendent Hennessy, an old RIC man, says: “It’s hard to convince the GAA that we’re not still the bloody peelers.” And “we try not to stir up too much recent history”. Like most books set in the past, The Branchmanhas resonance with the present moment.

The originality of this novel lies in O’Mahony’s treating of dirty work in Co Galway in 1925 within many of the conventions of American private eye fiction. I suspect that Nessa is, like myself, a fan of the peerless Raymond Chandler. Her hero, Michael Mackey – the Branchman – has to go down mean streets, without being mean himself. Like Philip Marlowe, he can exchange blows and shots when required, but he resembles Marlowe also in his stubborn principles and his romantic attachment to a tough broad.

The device allows O’Mahony to enliven the dialogue with wisecracks, especially from Sergeant Joe Costello, a fan of American pulp novels. Costello remarks of the station files, “I do like a bit of fiction now and then,” and, as the body count rises, “there are only so many suspects to go around”. In his role as desk sergeant, Costello epitomises a self-serving institutionalised policeman who could easily belong to Chandler’s Bay City police district. We see him as preoccupied with his tea and sandwiches, controlling communications inside and outside the barracks. Many scenes end with him “lifting the phone”. Or “replacing the receiver”. Her use of tough banter is a clever vehicle for O’Mahony’s major theme: how cynicism has supplanted idealism among the servants of the newly established Free State.

One classic fiction plot is built on the arrival of a newcomer into a tight-knit society, whereby long-dormant quarrels revive. Here Mackey is an unknown quantity, inevitably mistrusted by all the local gardaí as the guy from headquarters with fancy ideas. “Nobody told anything straight, it seemed.” Like Marlowe, an outsider but sufficiently in the know to upend a society where everyone has something to hide, everyone is tainted by a time of violence and treachery which, as Mackey discovers, has not ended. His quest is, overtly, to uncover an informer within the guards, but also to come to terms with his own burden of memory and guilt. He is a wounded and imperfect hero, with a leg injury from his service in the First World War, service of which he – in common with many other Mayo men and indeed Irish men – dare not speak. He is troubled also by memories of, and unfinished business from, dark deeds done during the War of Independence and the Civil War. Nor is his concealment of his service on the Western Front the only amnesia: many episodes from past struggles hover on the margins of conversation, as characters rationalise the choices they made and endure the consequences.

In his reflective self-awareness, Mackey contrasts with his opposite number, who has also just returned to the scene of many killings. He is a kind of shadow to Mackey – the guy who got the girl that Mackey fancied. Richie Latham appears initially as a tall figure in the long coat that is shorthand for a senior republican leader – as for instance in the recently screened RTÉ TV series Resistance. There, once the fictional hero Jimmy Mahon becomes a lieutenant of Michael Collins, he adopts a respectable formal wardrobe, including a long coat. Richie Latham has changed from diehard freedom fighter into gangster. He is still charismatic and sexy, but a bad egg, driven only by cruelty and pursuit of personal gain.

The reader is struck by idioms that belong to later periods than the 1920s, including some from our current discourse: (“back in the day”, “hospitality industry”, “be our guest”, “check it out”, “any time soon”, “give us a bell”, “get-out clause”, even “scarce garda resources”). Initially, I found this irritating, but I came to appreciate how it avoids the difficulty of stilted “historical” speech, and also conveys a sense of continuity with twenty-first century cliché – again, the resonance with today. The use of “Ms” in a couple of instances did strike me as too much of an anachronism: part of the credibility of the character of Annie Kelly stems from her image as a respectable young single woman, who has to be a “Miss”.

Whilst there are many, men and women, who are no better off as a result of independence, this is emphatically a man’s world. Neither in the barracks nor the bar (The Mount), where important conversations happen, are women taken seriously. Annie Kelly is lightly sketched, but emerges as a key actor: resilient and resourceful. She contrasts with the few other female characters, usually discounted or downtrodden.

In another resemblance to Chandler, the plot is busy, with a high body count, the consequence of “too many guns and too few brains”. The attentive reader may at times feel slightly more in the know than Mackey. The threads of the story come together, with some sudden twists. Amongst the set pieces: the big shootout at one of several bleak farmhouses, a deathbed confession and an official visit by Kevin O’Higgins – real-life minister for justice – work particularly well. Again, resonant in the light of later events.

1/3/2019

Pauline Hall is a regular contributor to the Dublin Review of Books. Her most recent novel is Eoin Doherty and The Fixers (2016).

Crimereads features The Branchman

Thanks to Paul French who included The Branchman in a Crimereads feature on Crime-writing about Galway - here's what he said:

Finally, there’s poet and teacher Nessa O’Mahony’s The Branchman (2018), a political thriller set in Galway in 1925 and featuring Detective Officer Michael Mackey of the newly-created Special Branch. Mackey has been sent to the Garda Barracks in Ballinasloe (a town near Galway) to root out subversives. The book is rich in detail thanks to the fact that O’Mahony, who is a Dubliner rather than a Galwegian, has previously meticulously researched the life of her own grandfather Michael McCann, who was an early member of the young Irish Free State’s Garda Síochána and posted to Galway.

And here's the link to the full article https://crimereads.com/the-crime-fiction-of-galway/?fbclid=IwAR2QXZUkywbsOQYOhRdYOb__1vWmyDTdQNEpVsOh3h5PjZ8RwEmhDulglfs