Where to buy books

Signed copies of the The Branchman are available direct from the author, at a cost of €22 (including post and package) within Ireland, €27 for other territories - payment to Paypal PayPal.Me/nessaom1964 and emailing details of addressee to omahony.nessa@gmail.com.

The Branchman can be bought in the following good bookshops:

Hodges Figgis, Dawson Street, Dublin 2.

Gutter Bookshop, Cow Lane, Temple Bar, Dublin 8.

Gutter Dalkey, Dalkey, Co. Dublin

Books Upstairs, D'Olier Street, Dublin 2.

Chapters Bookshop, Parnell Street, Dublin 1.

The Company of Books, Ranelagh, Dublin 6

Raven Books, Blackrock, County Dublin.

Rathfarnham Bookshop, Rathfarnham Shopping Centre, Dublin 14.

Antonia's Bookshop, Trim, Co. Meath.

Maynooth Bookshop, Maynooth, Co. Kildare

The Blessington Bookstore, Blessington, Co. Wicklow

The Nenagh Bookshop, Nenagh, Co. Tipperary.

Kerr's Bookshop, Clonakilty, Co. Cork.

Woodbine Bookshop, Kilcullen, Co. Meath.

Sheela na Gig bookshop, Cloghjordan, Co. Tipperary

The Castle Bookshop, Castlebar, Co. Mayo

The Reading Room, Carrick on Shannon, Co. Leitrim

The Book Centre, Waterford.

The Book Centre, Wexford.

Charlie Byrne's Bookshop, Galway City.

Salmon's Bookshop, Ballinasloe, County Galway.

P. Commane Books, Tralee. Co. Kerry

No Alibis, Belfast, Northern Ireland.

Fitz-Gerald's Bookshop, Macroom.

Kenmare Bookshop

A Novel Idea, Donegal

Farrell and Nephew, Newbridge, Co. Kildare

O'Mahony Booksellers, Limerick and online at https://www.omahonys.ie/the-branchman-p-10431546.html

Kennys Bookshop, Galway City and online at Kennys.ie.

Alan Hannas Bookshop, Rathmines, Dublin 6 and online at http://www.alanhannas.com/Search.asp?SearchTerm=Nessa%20O%27Mahony

The Book Depository at https://www.bookdepository.com/Branchman-Nessa-OMahony/9781851321896?ref=grid-view&qid=1536127623818&sr=1-3

Splendid review of The Branchman in The Irish Times

Declan Burke reviewed The Branchman in Saturday's Irish Times (1st December 2018) and offered this wonderful appraisal o the novel:

The Branchman

Poet Nessa O’Mahony publishes her debut crime novel with The Branchman (Arlen House, €15), which opens in 1925 with Michael Mackey, a detective officer in the newly formed Garda Special Branch, sent to the Garda barracks in Ballinasloe “to root out subversion”. Mackey, a veteran of numerous conflicts, isn’t fooled by the beauty of rural Galway: “It all looked innocent enough, but who knew what old animosities were lurking in those green fields?” There’s enough animosity to deliver a murder, certainly, and Mackey quickly discovers himself investigating the theft of a cache of stolen arms. O’Mahony is particularly strong on the everyday detail of a stranger negotiating a hazardous landscape – the character of Mackey is loosely based on her own grandfather, Michael McCann – and delivers a series of brief, intense chapters which generate a ferocious pace. Most fascinating, perhaps, is O’Mahony’s evocation of the wider political backdrop, that fragile, imperfect peace that took hold in the wake of the War of Independence and the Civil War.

The Branchman gets its Belfast launch

My new novel, The Branchman, got a splendid launch at the Crescent Arts Centre in Belfast on Friday 16th November, alongside new works of poetry by Natasha Cuddington and Grainne Tobin, also published by Arlen House.

Introducing the novel, Belfast journalist, novelist and memoir-writer Malachi O'Doherty called it 'a rattling good story' that 'more than being just a story ... is a profile of Ireland at a dodgy time, a comment on who we are and where we have come from'. The full launch speech follows:

"Imagine a time in a country's history after it has agonised for years about its place in a Union of nations. Some now feel that their vision of sovereignty has been betrayed, that they have had to settle for a shoddy compromise far short of the noble conception of a free and independent people, taking their place among the nations of the world. And others feel that the deal was the best that could be managed, and anyway, what's done is done.

So we find the characters in Nessa's novel in the 1920s not reconciled yet to the new Ireland, struggling to establish a country that functions with viable civic structures and a committed law abiding citizenry. All that seems a long way off. But it's not just the failure to completely leave the UK that rankles. The previous decade has seen an uprising and three wars. The Easter Rising, the Great War in Europe, the war for Irish independence and the Civil War. One character even recalls the Boer War. And while some of the characters we meet early in this book are jaded and reduced to a maudlin pettiness, others are trying to knock the new country into shape and others still are plotting to fight on.

This is a country in which a former British soldier turned IRA man, now a detective - Mackey - has some fine skills developed in harsh conditions but also has secrets that can drag him down. One of them is that British Army past, a mark of shame in the new Ireland. Put him in a country Garda station - like the one McGahern described in the Barracks - and see if he can get any bloody work done around here as the crime rate soars. Indeed, he is only going to get the blame for that himself.

In a small Irish town, everyone knows everyone else yet no one knows anything.

Why, who's asking?

The desk sergeant has all the gossip and no sympathy. His boss spends most of his time in the snug in the Mount and is so friendly with everyone that he can hinder investigations into respected citizens and party donors. He's up to something.

And there is a beautiful woman, who knew Mackey in his past, up in Mayo, in the trouble times and she's now in town.

And through all this move the secretive plotters, the killers and robbers, kidnapping and killing those who get in their way, preparing for the big one. But we'll not give away any more than that for now.

One tends to think that historical crime fiction is a genre that starts with Conan Doyle's Sherlock Holmes, that the rattle of cartwheels and clip of shod hooves over cobbles through gaslit mists is the perfect backdrop to crime, forgetting that Holmes was a contemporary of Doyle's who was reproducing the world of his own day, that it is in retrospect that we are enchanted by city smog and hackney cabs. Yet the past seems the perfect place for a mystery, it is a place in which our cultural bearings don't quite work.

Nessa is a bit more like Benjamin Black, but he takes us to more recent times in which a man might have more access to a motor car, even own one. Nessa takes us further back and recreates a world in which an investigator limps on foot, takes a train or rides a bicycle, in which calling at a woman's door at night might bring disgrace upon her but running a police station from the snug of a bar can be indulged as normal.

We have the small town by the docks, the one hotel and bar, the doctor who does both post mortems and house calls, if he's in the mood, and the weight of a drab culture of taking life at a slow pace and not fretting about very much lest it only lead to you having more work to do, more forms to fill in, more explanations to offer to people above you who are just as venal and lazy.

The gangster are as bad, well capable of staving your head in but sometimes just forgetting to.

So what is this book about?

It's a rattling good story, with secret machinations, murder and jealousy and love.

But to mind mind it is about the moment in the evolution of a nation after war, and in the first fumblings of independence, before it has learnt responsibility, before it has freed up imagination and started to grow, where the possibility still exists that the independence it fought for is more than it can manage.

This book comes at a time of a great flourishing of Irish fiction.

It is daring at such a time to write genre fiction, a crime novel. To pull that off you need not just clever plotting and plausible situating, you also need to be able to conceptualize human evil and human decency both.

Who knew Nessa had such badness in her?

But more than being just a story, this is a profile of Ireland at a dodgy time, a comment on who we are and where we have come from."

Malachi O'Doherty

Crescent Arts Centre, 16 November 2018

First print review in for The Branchman - and it's a corker

Murder and subversion in Ballinasloe

Galway Advertiser, Thu, Nov 08, 2018 - Kevin Higgins

NESSA O'MAHONY is primarily a poet, the author of three well received collections, and a verse novel. Much of her previous writing has interrogated the subjects of family and history, often dealing in quite innovative ways with how the two intersect.

In her 2014 poetry collection, Her Father’s Daughter, she published a parallel sequence of poems - one relating to her relationship with her own father, whose decline and passing she charted with sometimes aching candour, the second exploring the life of her grandfather, whose story emerges through her mother’s memories and O’Mahony’s own research.

Her latest work, The Branchman, published by Arlen House, is O’Mahony’s first foray into the historic crime thriller genre. Her above mentioned real life grandfather, Michael McCann, returns in fictional form as Michael Mackey, detective officer in the Garda Special Branch which has just been invented by the first Garda Commissioner, and future Adolf Hitler fanboy, General Eoin O’Duffy, and my own near namesake, Minister for Justice, Kevin O’Higgins.

The year is 1925 and O’Mahony’s protagonist is sent to the Garda barracks at Ballinasloe, his main task being “to root out subversion”, of which there was plenty in the aftermath of the Civil War. In this context the word “subversion” was most often a word used by the winners – Cumann na nGaedheal and their allies – to describe those they had recently defeated – the anti-Treatyites – but failed to actually kill or drive out of the country. The novel begins with a quite horrible murder, the investigation of which is first item on the agenda for Mackey upon his arrival in Ballinasloe.

One of the best things about this novel is O’Mahony’s masterful bringing back to life of places like Ballinasloe in the middle bit of the 20th century. An early part of Mackey’s settling into everyday life there is his struggle to find a place to have a quiet drink; no easy task for a Special Branch man, then or now. His superintendant recommends a suitable establishment, though warns that there must be “no shop talk” while imbibing: “The barman knew how to pull a pint, thank god. And the whiskey was Gold Label, even better. One-horse towns had their compensations.”

O’Mahony makes real the settling political sands of the time. Mackey’s own personal history illustrates this well. In 1915 he enlisted in the Royal Munster Fusiliers to fight for Britain in the World War I. In 1917, after the last of the executions of the leaders of the 1916 Rising, he joined the Volunteers (soon to become the IRA ) and was sent to Stockon-On-Tees where his task was to engage in “Arson and arms raids, mostly. The job was to distract rather than defeat...”

Come the Civil War, Mackey took the Pro-Treaty side and was stationed at Castlebar under the colourful, some would say notorious, General Sean McKeown whose job was to “pacify” the west of Ireland for the new Irish Free State. When he meets his ex almost girlfriend Annie on his arrival in Ballinasloe she quips, as is her way, “Detective...They let anyone into the Guards these days. As long as you were on the winning side, or at least claimed to be.” This is a big story expertly told.

Remembering Our Dead

100 years ago today (24th October 1918), my great uncle, Michael Walsh, a Private in the 115th regiment of the 3rd Battalion of the US Army, was killed by shrapnel during the Battle of the Meuse-Argonne. He was three weeks past his 30th birthday, and had only arrived in France the previous June. Members of my family, led by my sister, Finola, who has done extensive research into Michael's life and death, are visiting his grave at the Meuse Argonne American War Cemetery.

Age shall not weary them

in memory of Private Michael Walsh, 24/10/1918

St. Enda’s in its prime; sky clear, air crisp,

the sheddings of beech in piles

where the park warden swept them.

‘Brown gold,’ he smiles, undaunted

at a task made futile by the next gust.

We talk of public affairs; a presidential poll,

one candidate leading the field.

‘He’s 77,’ he shakes his head.

I think of my mother, all of ninety,

packing her bag today for a foreign trip,

to pay respects to a man she never met,

who died a decade before her birth,

peppered by shrapnel in a trench

on the French-Luxembourg border.

She’ll visit his white-crossed grave,

plant a marker, a poppy perhaps,

with her daughter and a scattering

of cousins from both sides of the Atlantic.

She’ll say a prayer, a poem,

cast a glance over row upon row

of white marble, tree-enclosed.

We shall not forget, how could we?

Shared genes give the same nose,

domed head, the pale blue eyes

that measure you up in an instant.

An instant was all it took

for Private Walsh, at 30 years old.

The cemetery will be swept,

poplars shedding tears

on the the living, on the dead

of the Meuse-Argonne.

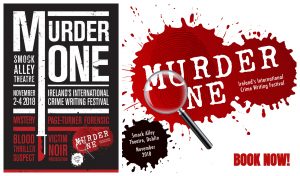

The Branchman debuts at Dublin's Brand New Crime Writing Festival

Dublin has a brand new crime writing festival. Murder One takes place over the weekend of 2nd-4th November, at the Smock Alley theatre, and features some of the leading crime writers from Ireland and abroad. Headliners are Michael Connelly (whose show is now sold out), Lynda La Plante and Peter James, but there's plenty of home-grown talent too. I'm delighted to say I'll be reading as part of the Speakers Corner sessions that take place throughout the weekend. I'm up first on the Saturday morning, at 11am, and will be reading from The Branchman, my new crime novel. http://www.murderone.ie/author-programme/free-readings-in-the-banquet-hall/

The man behind the Branchman - Michael McCann

Five years ago I began to research the life of my grandfather, Michael McCann, a man who has haunted much of my creative writing since I first heard my mother’s stories about his exploits during the War of Independence and Civil War, not to mention the first World War. I’d written about his war record in two poetry collections, but now I wanted to explore his fictional potential for a piece of crime fiction, and so honed in on his experiences as a policeman in newly independent Ireland.

Grandad left the National Army in 1924 and, like many other ex-soldiers, joined the nascent Garda Síochána. To get further background on that part of his career, I contacted the Garda Archive in Dublin Castle to ask if they had a record of him. By return of email came an A4 document that provided the bare minimum: his badge number, date of birth, date of appointment (March 28th, 1925), the stations and divisions where he served, monetary awards received (for good police duty) and date of discharge (March 29th, 1945).

The final entry related to his total service (some 20 years and two days), and the statement “Exemplary Service”. Never have two words been more frustrating; I wanted to hear the details of that service, the cases he’d investigated, the turmoil he’d witnessed in the early years of the new Free State. But if those records were still held anywhere, I wasn’t getting access to them.

There’s nothing a writer likes more than a vacuum, because that’s what frees up the imagination and allows us to invent. I became convinced that if officialdom couldn’t give me the facts, some imagination backed up by historical research might help fill in the gaps. The more I read, the more it became clear that the new police force Michael McCann joined had been thrown into the deep end of an Irish society still deeply divided and lawless. What a perfect scenario for the fictional hero I was beginning to envisage.

Given the breadth of those divisions, the nature of the force tasked with guarding the peace was hugely important. In 1922, Gen Eoin O’Duffy and Kevin O’Higgins planned to establish a Civic Guard, or Garda Síochána, to replace the Royal Irish Constabulary. This force was to be unarmed and politically neutral, though answerable to the Government Minister responsible for their administration. By the end of 1924 and the beginning of 1925, with the Army scaling back (some 30,000 soldiers were made redundant and few had jobs to go back to), it was clear that this new unarmed police force might need strengthened resources.

As Conor Brady puts it in Guardians of the Peace, his history of the Garda Síochána, “some districts remained peaceful after the military had been withdrawn … huge areas of Cork, Kerry, Tipperary, Clare and the Border country immediately became open territory not only for the remaining active bands of Republicans who could find very good reason to rob banks on behalf of the Republic but also groups of ordinary armed bandits. There was, furthermore, a mushrooming problem of disbanded Free State troops turning to violent crime.”

O’Higgins and O’Duffy decided that a restructuring would be required to provide the sort of policing needed in a still highly unstable situation. So in 1925, the Garda Síochána and the Dublin Metropolitan Police were amalgamated and, as part of this newly unified body, a new entity was created, the ‘Special Branch’. The leader of this new outfit was to be David Neligan, one of Michael Collins’s original secret service agents and now a colonel in the Free State Army.

O’Higgins stipulated that members of the new armed detective team should be recruited from the Civic Guards and from the Free State Army Office corps. There were to be about 200 men in this new unit, divided between Dublin and 20 Garda divisions around the country. They were to be given six months of training in areas such as criminal law, police procedure, ballistic and forensic evidence and the use of firearms and self-defense.

My grandfather was appointed as a member of the Garda Síochána and joined the Special Branch on its formation shortly afterwards. He was stationed first in Letterkenny, before being moved to Ballinasloe in 1929, where he spent the majority of his career.

Although the Civil War had been over for several years, the Galway region was still pretty unsettled when my grandfather was transferred there. Ammunition left over from the conflict could cause security problems. On March 1st, 1930, there was a major blast at the back of Society Street in Ballinasloe, which led to the demolition of some shop fronts and the destruction of the offices of the local newspaper, The East Galway Democrat. As The Irish Times reported, “investigations were made by the Civic Guards, and it is thought that a land mine, which was probably hidden by someone who wanted to get rid of it in an ash pit or somewhere behind Society Street, was accidentally exploded”. Later that year, an Irish Omnibus Company vehicle travelling from Galway to Athlone was fired upon from a field on the Athenry to Ballinasloe road. And in September 1931, the Civic Guard barrack at nearby Kilreekil was blown up.

The more I read, the more it became clear that the new police force Michael McCann joined had been thrown into the deep end of an Irish society still deeply divided and lawless. Trouble never seemed too far away in Ballinasloe in those days. In April 1935, The Irish Times reported that that three shots had been fired into the house of Michael Killeen, Brackernagh. Mrs Killeen, who had been sitting near the sitting-room window, narrowly avoided injury. At a military tribunal the following month, John Keogh of Deerpark, Ballinalsoe, was tried and sentenced to two years in prison for the attack on Killeen, who had been secretary of the Poolboy and Kellysgrove Peat Development Association. In 1941, my grandfather gave evidence in a court case involving a husband and wife in whose house guards had discovered a cache of ammunition and bank notes. According to press reports, Michael had been part of a group searching the house and had discovered the cache “in a groove cut out of the leg of the table”.

My uncle, Liam McCann, (now deceased) also remembered an event from the early 1930s. There had been a hurling match in Duggan Park in Ballinasloe. It got out of hand and my grandfather arrested a man and brought him down to the barracks. A mob came down to try and storm the barracks and Granddad had to fire a gun over their heads to disperse the crowd.

So there was no shortage of incidents that could fuel the fiction I was planning to write. My novel, titled The Branchman and published this month by Arlen House, incorporates some of them and invents many others. It features a newly appointed Special Branch Detective called Michael Mackey, assigned to the Ballinasloe police barracks with the task of discovering the subversives at work there. Of course he bears more than a passing resemblance to my grandfather but, as with many fictional heroes, has his own characteristics, flaws and plot points, which almost certainly never happened in real life, or at least not in the way I tell them here. But that is the joy of historical fiction; it presents an alternative reality. If the writer can make the reader believe in that reality, at least from the first page to the last, she has succeeded in her task.

As this decade of commemoration advances, more and more stories are being unearthed about the unstable society that the new Free State attempted to pacify in the aftermath of Civil War. It’s a rich subject for fiction; I look forward to reading the many imaginative responses that will undoubtedly follow.

A version of this article first appeared in the Irish Times on 19th September 2018.

Copies of The Branchman now on Pre-order

Delighted to say that copies of The Branchman can now be pre-ordered on Book Depository at

https://www.bookdepository.com/Branchman-Nessa-OMahony/9781851321896?ref=grid-view&qid=1536127623818&sr=1-3

I was delighted to be asked to contribute ten poems to UCD's splendid Irish Poetry Reading Archive. The link to the Youtube recordings are here: http://libguides.ucd.ie/ipra/readingsotor

A novel new experience

Although I've focussed on poetry throughout my writing career, I've always been an avid reader of fiction, and much of my poetry has tended towards the narrative. So it was only a matter of time before I ventured into the brave new world of fiction writing. That I should want to write crime came as no surprise to me; my earliest reading as a young teenager was the novels of Agatha Christie; I worked my way through P.D. James, Ruth Rendell and though I never read Colin Dexter's novels, I became addicted to the TV adaptation of his Chief Inspector Morse (and the sequels and prequels that followed).

I've always believed that we should write what we enjoy reading, so in 2015 I took my courage in my

hands and signed up for a course in crime fiction with Irish thriller-writer, Louise Phillips. In an incredibly instructive 10 weeks, Louise took us through the intricacies of structure, suspense, hooks and dialogue. Her first piece of advice was the most crucial; she pointed out that if you wrote 500 words a day, you'd have a full-length novel within the year. She encouraged us to email her our weekly word count, and even provided a handy grid so that we could fill out our daily rate. I got up at 5.30am and wrote until 7am every morning that course ran, and had the best part of 20,000 words written before it had ended. It took me another two years to complete the remaining 60,000 and another year again to edit, refine, edit again to the point that I was ready to send it out.

So i was thrilled when Irish publisher Alan Hayes of Arlen House said he'd like to publish the book, The Branchman, which is soon to make its first appearance in the world.

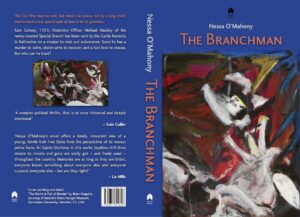

So what's it about? It's about a Special Branch Detective, Michael Mackey, who is sent to a small East Galway town to uncover a nest of subversives and a possible traitor within the police station to which he has been assigned. It's about the utterly lawless world of post Civil War Ireland, where nearly everyone had a gun, or a secret, or both. It's about murder and love and jealousy.

I enjoyed writing it enormously, wanting above anything else to create a story that people would want to finish, pages they'd want to turn and characters they'd come to care about. I hope you enjoy The Branchman. There's more where that came from.

The Branchman will be launched by novelist Catherine Dunne at 6.30pm on Tuesday 18th September, alongside new work by Mary O'Donnell and Sophia Hillan, at the Irish Writers Centre, Parnell Square, Dublin 1.