Launching a new poetry collection - The Hollow Woman on the Island

We had great fun launching my fifth poetry collection, The Hollow Woman on the Island, at Poetry Ireland on 28th May. I was in excellent company, as Jo Slade and John Murphy were also launching new volumes with Salmon Poetry, our publisher. I was also incredibly lucky to have the amazing Katie Donovan as my 'launcher' - here's her very generous comment on my new book, which can be ordered online from Salmon's website at https://www.salmonpoetry.com/details.php?ID=509&a=281

"Themes of family, mortality, faith and art inform this new collection from Nessa O’Mahony. Although the title, The Hollow Woman on the Island, suggests loss and limbo, the book rings with birdsong, the fluting of an old gate in the wind, family anecdotes from Cork to Vienna, and concludes: “prayer starts in the same place as story”.

Many years ago, Nessa’s bright enthusiastic face and incisive comments lit up my Creative Writing class in the IWC. Her consistent output ever since – from four volumes of poetry to her novel, The Branchman, and her work as an editor of two anthologies - has brought her to the centre of the writing scene in Ireland and abroad. This is her fifth collection of poetry – another book to be proud of. And may I say, as her former “teacher”, how proud I am as well.

There are several powerful poems in The Hollow Woman on the Island that give voice to a fear so many of us have known, as doctors hover with scalpels and jargon, offering “butcher’s cuts of possibility”.

The unbearable, post-surgery lightness which, for a woman who has lost her fertility, is so cruelly ironic in its ovoid shape, is expressed beautifully and heart-wrenchingly in the title poem. A similar delicate approach is evident in “Alcmene’s Dream”, which ends with an absent cradle, and first appeared in Metamorphic, the anthology of poetic responses to Ovid which Nessa co-edited in 2017.

With the beautiful poem in celebration of her niece’s wedding, Nessa brings this theme to bear on the larger picture of a family and its collective fertility – the significance of the role of each member within that circle.

Nessa’s well-known gravitational pull towards history is evident in many of the poems, one of the most eloquent being “O’Leary’s Grave” where some of Ireland’s shamefully large population of homeless citizens bed down in Croppies Acre while a scene is shot for a movie about The 1916 Rising.

Her capacity to depict landscape with the deft shapes and colours of a painter’s eye is also in evidence, from the Bohea Stone in Mayo to Cill Rialaig in Co Kerry, and our own local river, the Dodder. Wildlife abounds, from fledgling wrens to otters and hares.

Wisdom, lightness of touch, vulnerability, craft and ironic flourishes. Family, travel, friendship and political awareness. There is much to mine in this new work.

Finally, I like how she chooses to end the collection, with a vision of Homer as a woman. For we know that Homer represents a collective circle of narrators, within a large family of storytellers, each with a vital contribution to make to the endeavour as a whole."

Katie Donovan, at Poetry Ireland, 28th May 2019.

Discussing the creative response to historical events in early 20th century Ireland

I recently gave a paper at the inaugural Association of Writing Programmes Ireland conference at University College Dublin about the challenges of writing historical fiction - I was part of a panel with novelist Mary O'Donnell, who discussed the writing of her recent short fiction collection, Empire (Arlen House 2018). There was some fascinating discussion afterwards so I'm posting my paper here:

FINDING THE FICTIVE SPACE WITHIN CONTESTED FACT

As our abstract has suggested, the current Decade of Commemoration has brought into the open many stories previously hidden from the narrative mainstream of received history. In my presentation I am focussing on the creative response to the convulsive events of the first quarter of the 20th century, namely World War I, the Rising and War of Independence and Civil War, using my own experiences as a creative writer as the main basis of discussion, and seeking to place that practice in the tradition of how others have responded imaginatively to the period.

In this presentation, I’ll consider the issues around the creative response to factual events in the first quarter of the 20th century, before focussing on my own experience of writing the first novel in a trilogy exploring the experiences of an ex-army turned policeman in the Irish Free State. When I began this paper, I had a fairly clear outline of what I intended to cover. But that was before the events in Derry last week when journalist and writer Lyra McKee was shot dead during rioting in the Creggan, when a paramilitary took aim at police and killed her instead. That event reminded me that politically-inspired violence in Ireland is not confined to history, and that writers continue to have to grapple with the legacy of our confused and contested past. I’ll return to that point at the end of this paper.

Understanding the past is crucial, and when you begin to write historical fiction, you quickly realise the limits to your knowledge of history. I was speaking to another writer recently about how we were taught the subject. She, a generation ahead of me, mentioned that secondary school history had stopped at the Tudors. In a brief addendum, the 1916 Rising was mentioned as having taken place, but no future details were provided. This was in the 1960s, when the events at the GPO and elsewhere were not even half a century old. I studied history at school in the 1970s, and took it as a subject at university here in Belfield in the early 80s. By that stage, there were plenty of accounts of the Easter Rising, and whole text books consisted of a chronology of rebellions from the Flight of the Earls to Soloheadbeg, that suggested the only possible relationship between Ireland and England was a dysfunctional one, with uprisings the inevitable and sole solution. This kind of history focussed on the minority of men and women involved in the planning of those uprisings; little account was taken of the majority of the population whose lives were of course affected by political events but who went on with their day to day routines as best they could – the one exception were the lectures of Mary Daly, who crucially conveyed the social history in an admirably compelling way. But, by and large, the stories of everyday men and women of the period remained untold.

By the historians, that is.

Writers were a different matter, and although literature of the political unrest was not numerous during the early decades of the 20th century, there were notable exceptions. Yeats, of course, gave us his own idiosyncratic take on violent nationalism. Sean O’Casey’s plays represented ordinary men and women caught up in extraordinary events. Juno and the Paycock tackled the harsh brutalities of life during the Civil War – his Shadow of a Gunman attracted enormous contemporary criticism for its unvarnished depiction of both revolutionaries and Dubliners. Liam O’Flaherty’s The Informer, published in 1925, won the James Tait Black Memoiral Prize that year for his depiction of Gypo Nolan, the eponymous informer who goes on the run in the Civil War. In 1929, Elizabeth Bowen published The Last September, which told the story of the Anglo-Irish family The Naylors against a backdrop of the War of Independence. In 1931, Frank O’Connor published his short story “Guests of the Nation,” in a collection of the same name. For many years this was considered the seminal story of the War of Independence, telling as it did the story of two British soldiers shot dead by the Irish Volunteers during the War of Independence. It was certainly the only story dealing with the period that was on the curriculum when I was at school.

But in the 30s, it seemed to go silent. Scholars will have their theories about why the period between 1930 and 1970 did not produce more writing about the bloody events that had given birth to the Irish Free State and then Republic. De Valera’s Ireland did not encourage much self-reflection or social scrutiny so writers may have preferred to cast their nets elsewhere – one thinks of the surreal satire of Flann O’Brien, or the medieval monastic whimsy of Mervyn Wall’s Unfortunate Fursey.

It’s certainly possible that the Censorship Board, established in 1929, might also have had something to do with. Although its remit was the safeguarding of ‘public morality’ through the banning of obscene literature, it soon became clear that the Censor took a very broad view of what constituted ‘obscene’ and soon was banning anything that might challenge a very narrow public consensus. In such a climate, it was hardly likely that Irish writers would seek to challenge political orthodoxies.

And so it remained until the mid-60s, when the social climate began to change and slowly, gradually, people began to challenge nationalist pieties in a way that would have been unthinkable previously. The historians may have started writers rethinking their approach – when I studied history here at UCD in the early 1980s, revisionism was only beginning to make itself felt, and early work by Ruth Dudley Edwards, amongst others, began to suggest that we might find other ways of looking at long-held truths, though that was not the consensus view by any means. Creative writers may have been emboldened by that revision.

But it was an uncomfortable time to be doing so. The Northern Ireland Troubles were under way, and from my very youthful perspective at the time, it felt like there were divided loyalties in the Republic. We still liked to cheer whenever the British got beaten in any sport, but, depending on your viewpoint, honouring our Fenian Dead could be seen as acknowledging a link between them and the current breed of paramilitaries responsible for such carnage on both islands. How to reconcile that sort of cultural ambivalence, and how to write about it creatively?

I don’t have the scope in this paper to discuss the literature of the Northern Irish Troubles. Given that my own creative focus has been on the first quarter of the 20th century, since I began to explore in fiction the lives of the men and women caught up in the various conflicts of that period, that’s what I want to discuss now.

Julian Gough once courted controversy by stating that Irish novelists were obsessed with the past. Writing in his blog in 2010, he said: The older, more sophisticated Irish writers that want to be Nabokov give me the yellow squirts and a scaldy hole. If there is a movement in Ireland, it is backwards. Novel after novel set in the nineteen seventies, sixties, fifties. Reading award-winning Irish literary fiction, you wouldn't know television had been invented. Indeed, they seem apologetic about acknowledging electricity.” (https://www.theguardian.com/books/2010/feb/11/julian-gough-irish-novlists-priestly-caste accessed 18/4/19)

Gough rowed back on his comments a little later, but it’s interesting to consider, even in his commentary, the lack of focus on the earlier part of the 20th century. Where were the contemporary novelists who were writing about that period (Apart from Jennifer Johnston’s How Many Miles to Babylon, published in 1974 and still one of the finest Irish novels about the Great War)?

The decade of commemoration acted as a galvanising force, it would seem. Two things were going on here. Firstly, the more the public discourse turned to considering and reconsidering the events of 100 years ago, the more writers began to explore that world imaginatively. Secondly, I’m sure there was a commercial imperative. Publishers are quick to see the attractions of anniversary-themed books (think how many books came out this year around the theme of female suffrage and forgotten women) so they may have been more open to proposals around historic themes. It can be no coincidence that over the past two decades we’ve seen books by Roddy Doyle (His The Last Roundup Trilogy which began with A Star Called Henry, 1999), Lia Mills (Fallen), Sebastian Barry (A Long, Long Way), Mary Morrissy (The Rising of Bella Casey) and, in the crime/thriller field, series by Kevin McCarthy and Joe Joyce among others. Nicola Pierce and Sheena Wilkinson have been exploring the period for children and young adult fiction.

For me as a poet and novelist, it seemed inevitable that I would be drawn to the period. I grew up hearing about the adventures of men and women in that period of time. My mother is a terrific storyteller and my childhood was filled with accounts of my grandfather’s exploits in the War of Independence, and the Civil War. When I began to write, I quickly found that family history was an important subject matter for me. But there were gaps in my knowledge. Family history is never complete, particularly when reticence is part of the mix.

It was only when I began, five years ago, to professionally research the life of my grandfather, Michael McCann, that I discovered that there was considerably more to him than family history had told. Not surprisingly, those family stories had centred on his role as a Volunteer during the War of Independence, though details were sketchy even there, and as a Commandant in the Free State Army during the Civil War. There was practically no mention of the fact that he’d fought on the Somme in World War I – that part of his backstory had been carefully elided. But as we approached the centenary of the start of the First World War, I was anxious to fill in the gaps and, with the help of my surviving uncle, Liam McCann, who was in possession of Granddad’s soldier’s pocketbook, which gave his medal number, I was able to track down a fuller account of his involvement. He enlisted in 1915, joined the Royal Munster Fusiliers, and spent 1916 and part of 1917 on the Western Front, in particular the Somme. He was injured by shrapnel, and invalided out in late 1917. It was then that he moved to North East England, and joined a faction of the Irish Volunteers.

I had written about his Civil War activities in my second poetry collection (Trapping a Ghost, bluechrome 2005), but I’d never written about his First World War activities. Now, with the additional information I’d gained through research, I was able to write a series of poems that charted his progress through the war, and the legacy of injury it had left. Those poems appeared in my 2014 collection, Her Father’s Daughter; I used as the cover photo a snap of my grandfather in his Royal Munster Fusilier’s uniform. I’d not been aware of the photograph’s existence, nor had my mother, but was sent it by a second cousin I uncovered during online research into my grandfather’s family. On the night of the launch, I discovered that choice was not entirely uncontroversial. At the end of the evening, an aunt approached me, wondering why I hadn’t, instead, used one of the many photographs of Granddad in his Free State Army uniform. The family was not universally ready to accept the many-faceted nature of my grandfather’s history, it would seem.

And yet, that was precisely the point of writing those poems, and making use of that photo. My grandfather had not spoken at all about his First World War record, in common with the thousands of Irishmen and women who’d survived that bloody conflict, and who had come home to an Ireland ‘changed utterly’ and utterly unreceptive to their plight. If they did talk about it, they could be a target for political nationalists. So the safest thing to do was to stay quiet. I was convinced of the need to to reinstitute at least one of those voices, to claim that covert experience fighting for Britain as every bit as valid and worthy of writing about as the more politically acceptable activities that followed it.

The choice of my next book, a crime novel inspired by my grandfather’s 20-year career in An Garda Siochána, seemed a less controversial choice. There was more family anecdotal evidence to draw upon, as my mother and her siblings were around for most of it, but there were still gaps in their knowledge, stories half-remembered or conflated. And when I approached the Garda Archive in Dublin Castle to see if they had further information, they sent by return of email an A4 document that provided the bare minimum: his badge number, date of birth, date of appointment (28 March 1925), the stations and divisions where he served, monetary awards received (for good police duty) and date of discharge (29 March 1945). Oh, and the final entry, was a description of his total service as ‘Exemplary’. That could have covered a multitude.

As you know, there’s nothing a writer likes more than a vacuum, because that’s what frees up the imagination and allows us to invent. I became convinced that if officialdom couldn’t give me the facts, some imagination backed up by historical research might help fill in the gaps. The more I read of the background, from local newspaper reports and historical accounts, the more it became clear that the new police force Michael McCann joined had been thrown into the deep-end of an Irish society still deeply divided and lawless after the ending of the Civil War. It was a society I was deeply curious about, but one that I had rarely if ever read about. Thus it was one I wanted explore in fiction.

The background to the Special Branch that my Grandfather joined, and which is the subject of my novel, The Branchman, is as follows. In the period immediately after the end of the Civil War, Minister for Home Affairs Kevin O’Higgins and Garda Commissioner Eoin O’Duffy decided that a restructuring of the police force would be required to provide the sort of policing needed in a still highly unstable situation. So in 1925, the Garda Síochána and the Dublin Metropolitan Police were amalgamated and, as part of this newly unified body, a new entity was created, the ‘Special Branch’. The leader of this new outfit was to be David Neligan, one of Michael Collins’s original secret service agents and now a Colonel in the Free State Army.

My grandfather, Michael McCann, was appointed as a member of the Garda Síochána of 28th March, 1925, and joined the Special Branch on its formation shortly afterwards. He was stationed first in Letterkenny, before being moved to Ballinasloe in 1929, where he spent the majority of his career.

My fictional hero, Michael Mackey, was also appointed to the Special Branch in 1925, although he went straight to Ballinasloe to conduct his investigations into suspected subversives in the area. Although the plot is highly fictionalized, I did draw on actual events. For example, I’d read an article in the Irish Times archives that cached ammunition left over from the Civil War regularly caused security problems in small Irish towns. For example, 1st March, 1930, there was a major blast at the back of Society Street in Ballinasloe, which led to the demolition of some shop fronts and the destruction of the offices of the local newspaper, The East Galway Democrat. As The Irish Times reported, “investigations were made by the Civic Guards, and it is thought that a land mine, which was probably hidden by someone who wanted to get rid of it in an ash pit or somewhere behind Society Street, was accidentally exploded”. I took the kernel of this event for the novel, and an early incident involves Mackey discovering a cache of weapons in the murder victim’s coal shed, and engaging in a shoot-out with one of the subversives.

Another plot twist inspired by actual events came courtesy of my uncle, Liam McCann (now dead), who also remembered an event from the early 1930s. There had been a hurling match in Duggan Park in Ballinasloe. It got out of hand and my grandfather arrested a man and brought him down to the barracks. A mob came down to try and storm the barracks and Granddad had to fire a gun over their heads to disperse the crowd. In the novel, this gets translated into a major grudge match between two arch rival teams in a county final that occurs on the same day as a visit to Ballinasloe by Minister Kevin O’Higgins. The fans have been infiltrated by subversives who incite a riot that spills out into the official visit, with fatal consequences.

By the way, I am only too aware that my choice of terminology – of subversives and Irregulars – might seem to nail my political allegiances to the mast. The Free State authorities coined the phrase ‘Irregular’ for those men who were against the Treaty and formed their own military opposition to it. Those who grew up in that Anti-Treaty tradition would more likely refer to them as Volunteers, or Republicans, phrases that are as loaded today as they were then – the initial statement commenting on Lyra McKee’s death was attributed to Volunteers. But although my protagonist Michael Mackey might be in no doubt about who the ‘baddies’ were in 1925, the reader will gradually discover that things in the new Free State are not quite that black and white. People on all sides of the divide are forced to compromise morals and integrity on a regular basis; my choice of the crime genre provided me with a useful framework for such an exploration. Crime readers are used to depictions of corrupt societies where nobody is beyond suspicion; my use of a small Irish town as a microcosm for larger dark forces at play in a riven Irish society would not shock anybody familiar with those tropes. Indeed, a recent review of the book by novelist Pauline Hall recognized those similarities:

"The originality of this novel lies in O’Mahony’s treating of dirty work in Co Galway in 1925 within many of the conventions of American private eye fiction. I suspect that Nessa is, like myself, a fan of the peerless Raymond Chandler. Her hero, Michael Mackey – the Branchman – has to go down mean streets, without being mean himself. Like Philip Marlowe, he can exchange blows and shots when required, but he resembles Marlowe also in his stubborn principles and his romantic attachment to a tough broad."

But does writing in a recognizable tradition such as the crime thriller allow one license to mix fact and fiction in such a way? I would argue yes, although I’m aware that more than one reader (with connections to the town) has complained about the depiction of Ballinasloe people in the novel, although others had no such problem. I’d claim that novelists must engage with the past through their own imaginative filter. My protagonist bears more than a passing resemblance to my grandfather but, as with many fictional heroes, has his own characteristics, flaws and plot points, which almost certainly never happened in real life, or at least not in the way I tell them in the novel. But isn’t that is the joy of historical fiction; it presents an alternative reality. If the writer can make the reader believe in that reality, at least from the first page to the last, she has succeeded in her task.

Or so I thought before the events of last week in Derry City. Now I wonder whether writers have a duty to the past, to recognize that what might be considered finished business in some eyes is still very much alive and current and thus must be handled with greater care and attention. Might that explain the silence that descended upon Irish writers in the decades after the cessation of the Civil War, a reluctance to deal with what was very much still a source of live debate and dissention? Was it the ending of the Northern Irish Troubles in 1997 that freed up creative writers to tackle these subjects again? And will the arrival onto the scene of a new generation of paramilitaries still trying, in the words of Paul Brady, to ‘carve tomorrow from a tombstone?’ make us more hesitant to write about those events of 100 years ago?

I don’t have any answers to this. I know that as this decade of commemoration advances, more and more stories will be unearthed about the unstable society that the new Free State attempted to pacify in the aftermath of Civil War. It remains a rich subject for fiction; I hope I hold my courage to continue that imaginative exploration.

Thank you

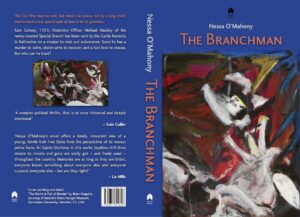

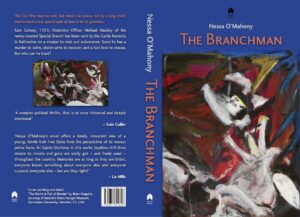

Crimereads features The Branchman

Thanks to Paul French who included The Branchman in a Crimereads feature on Crime-writing about Galway - here's what he said:

Finally, there’s poet and teacher Nessa O’Mahony’s The Branchman (2018), a political thriller set in Galway in 1925 and featuring Detective Officer Michael Mackey of the newly-created Special Branch. Mackey has been sent to the Garda Barracks in Ballinasloe (a town near Galway) to root out subversives. The book is rich in detail thanks to the fact that O’Mahony, who is a Dubliner rather than a Galwegian, has previously meticulously researched the life of her own grandfather Michael McCann, who was an early member of the young Irish Free State’s Garda Síochána and posted to Galway.

And here's the link to the full article https://crimereads.com/the-crime-fiction-of-galway/?fbclid=IwAR2QXZUkywbsOQYOhRdYOb__1vWmyDTdQNEpVsOh3h5PjZ8RwEmhDulglfs

Where to buy books

Signed copies of the The Branchman are available direct from the author, at a cost of €22 (including post and package) within Ireland, €27 for other territories - payment to Paypal PayPal.Me/nessaom1964 and emailing details of addressee to omahony.nessa@gmail.com.

The Branchman can be bought in the following good bookshops:

Hodges Figgis, Dawson Street, Dublin 2.

Gutter Bookshop, Cow Lane, Temple Bar, Dublin 8.

Gutter Dalkey, Dalkey, Co. Dublin

Books Upstairs, D'Olier Street, Dublin 2.

Chapters Bookshop, Parnell Street, Dublin 1.

The Company of Books, Ranelagh, Dublin 6

Raven Books, Blackrock, County Dublin.

Rathfarnham Bookshop, Rathfarnham Shopping Centre, Dublin 14.

Antonia's Bookshop, Trim, Co. Meath.

Maynooth Bookshop, Maynooth, Co. Kildare

The Blessington Bookstore, Blessington, Co. Wicklow

The Nenagh Bookshop, Nenagh, Co. Tipperary.

Kerr's Bookshop, Clonakilty, Co. Cork.

Woodbine Bookshop, Kilcullen, Co. Meath.

Sheela na Gig bookshop, Cloghjordan, Co. Tipperary

The Castle Bookshop, Castlebar, Co. Mayo

The Reading Room, Carrick on Shannon, Co. Leitrim

The Book Centre, Waterford.

The Book Centre, Wexford.

Charlie Byrne's Bookshop, Galway City.

Salmon's Bookshop, Ballinasloe, County Galway.

P. Commane Books, Tralee. Co. Kerry

No Alibis, Belfast, Northern Ireland.

Fitz-Gerald's Bookshop, Macroom.

Kenmare Bookshop

A Novel Idea, Donegal

Farrell and Nephew, Newbridge, Co. Kildare

O'Mahony Booksellers, Limerick and online at https://www.omahonys.ie/the-branchman-p-10431546.html

Kennys Bookshop, Galway City and online at Kennys.ie.

Alan Hannas Bookshop, Rathmines, Dublin 6 and online at http://www.alanhannas.com/Search.asp?SearchTerm=Nessa%20O%27Mahony

The Book Depository at https://www.bookdepository.com/Branchman-Nessa-OMahony/9781851321896?ref=grid-view&qid=1536127623818&sr=1-3

The Branchman gets its Belfast launch

My new novel, The Branchman, got a splendid launch at the Crescent Arts Centre in Belfast on Friday 16th November, alongside new works of poetry by Natasha Cuddington and Grainne Tobin, also published by Arlen House.

Introducing the novel, Belfast journalist, novelist and memoir-writer Malachi O'Doherty called it 'a rattling good story' that 'more than being just a story ... is a profile of Ireland at a dodgy time, a comment on who we are and where we have come from'. The full launch speech follows:

"Imagine a time in a country's history after it has agonised for years about its place in a Union of nations. Some now feel that their vision of sovereignty has been betrayed, that they have had to settle for a shoddy compromise far short of the noble conception of a free and independent people, taking their place among the nations of the world. And others feel that the deal was the best that could be managed, and anyway, what's done is done.

So we find the characters in Nessa's novel in the 1920s not reconciled yet to the new Ireland, struggling to establish a country that functions with viable civic structures and a committed law abiding citizenry. All that seems a long way off. But it's not just the failure to completely leave the UK that rankles. The previous decade has seen an uprising and three wars. The Easter Rising, the Great War in Europe, the war for Irish independence and the Civil War. One character even recalls the Boer War. And while some of the characters we meet early in this book are jaded and reduced to a maudlin pettiness, others are trying to knock the new country into shape and others still are plotting to fight on.

This is a country in which a former British soldier turned IRA man, now a detective - Mackey - has some fine skills developed in harsh conditions but also has secrets that can drag him down. One of them is that British Army past, a mark of shame in the new Ireland. Put him in a country Garda station - like the one McGahern described in the Barracks - and see if he can get any bloody work done around here as the crime rate soars. Indeed, he is only going to get the blame for that himself.

In a small Irish town, everyone knows everyone else yet no one knows anything.

Why, who's asking?

The desk sergeant has all the gossip and no sympathy. His boss spends most of his time in the snug in the Mount and is so friendly with everyone that he can hinder investigations into respected citizens and party donors. He's up to something.

And there is a beautiful woman, who knew Mackey in his past, up in Mayo, in the trouble times and she's now in town.

And through all this move the secretive plotters, the killers and robbers, kidnapping and killing those who get in their way, preparing for the big one. But we'll not give away any more than that for now.

One tends to think that historical crime fiction is a genre that starts with Conan Doyle's Sherlock Holmes, that the rattle of cartwheels and clip of shod hooves over cobbles through gaslit mists is the perfect backdrop to crime, forgetting that Holmes was a contemporary of Doyle's who was reproducing the world of his own day, that it is in retrospect that we are enchanted by city smog and hackney cabs. Yet the past seems the perfect place for a mystery, it is a place in which our cultural bearings don't quite work.

Nessa is a bit more like Benjamin Black, but he takes us to more recent times in which a man might have more access to a motor car, even own one. Nessa takes us further back and recreates a world in which an investigator limps on foot, takes a train or rides a bicycle, in which calling at a woman's door at night might bring disgrace upon her but running a police station from the snug of a bar can be indulged as normal.

We have the small town by the docks, the one hotel and bar, the doctor who does both post mortems and house calls, if he's in the mood, and the weight of a drab culture of taking life at a slow pace and not fretting about very much lest it only lead to you having more work to do, more forms to fill in, more explanations to offer to people above you who are just as venal and lazy.

The gangster are as bad, well capable of staving your head in but sometimes just forgetting to.

So what is this book about?

It's a rattling good story, with secret machinations, murder and jealousy and love.

But to mind mind it is about the moment in the evolution of a nation after war, and in the first fumblings of independence, before it has learnt responsibility, before it has freed up imagination and started to grow, where the possibility still exists that the independence it fought for is more than it can manage.

This book comes at a time of a great flourishing of Irish fiction.

It is daring at such a time to write genre fiction, a crime novel. To pull that off you need not just clever plotting and plausible situating, you also need to be able to conceptualize human evil and human decency both.

Who knew Nessa had such badness in her?

But more than being just a story, this is a profile of Ireland at a dodgy time, a comment on who we are and where we have come from."

Malachi O'Doherty

Crescent Arts Centre, 16 November 2018

Remembering Our Dead

100 years ago today (24th October 1918), my great uncle, Michael Walsh, a Private in the 115th regiment of the 3rd Battalion of the US Army, was killed by shrapnel during the Battle of the Meuse-Argonne. He was three weeks past his 30th birthday, and had only arrived in France the previous June. Members of my family, led by my sister, Finola, who has done extensive research into Michael's life and death, are visiting his grave at the Meuse Argonne American War Cemetery.

Age shall not weary them

in memory of Private Michael Walsh, 24/10/1918

St. Enda’s in its prime; sky clear, air crisp,

the sheddings of beech in piles

where the park warden swept them.

‘Brown gold,’ he smiles, undaunted

at a task made futile by the next gust.

We talk of public affairs; a presidential poll,

one candidate leading the field.

‘He’s 77,’ he shakes his head.

I think of my mother, all of ninety,

packing her bag today for a foreign trip,

to pay respects to a man she never met,

who died a decade before her birth,

peppered by shrapnel in a trench

on the French-Luxembourg border.

She’ll visit his white-crossed grave,

plant a marker, a poppy perhaps,

with her daughter and a scattering

of cousins from both sides of the Atlantic.

She’ll say a prayer, a poem,

cast a glance over row upon row

of white marble, tree-enclosed.

We shall not forget, how could we?

Shared genes give the same nose,

domed head, the pale blue eyes

that measure you up in an instant.

An instant was all it took

for Private Walsh, at 30 years old.

The cemetery will be swept,

poplars shedding tears

on the the living, on the dead

of the Meuse-Argonne.

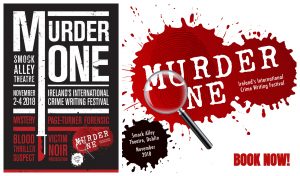

The Branchman debuts at Dublin's Brand New Crime Writing Festival

Dublin has a brand new crime writing festival. Murder One takes place over the weekend of 2nd-4th November, at the Smock Alley theatre, and features some of the leading crime writers from Ireland and abroad. Headliners are Michael Connelly (whose show is now sold out), Lynda La Plante and Peter James, but there's plenty of home-grown talent too. I'm delighted to say I'll be reading as part of the Speakers Corner sessions that take place throughout the weekend. I'm up first on the Saturday morning, at 11am, and will be reading from The Branchman, my new crime novel. http://www.murderone.ie/author-programme/free-readings-in-the-banquet-hall/

The man behind the Branchman - Michael McCann

Five years ago I began to research the life of my grandfather, Michael McCann, a man who has haunted much of my creative writing since I first heard my mother’s stories about his exploits during the War of Independence and Civil War, not to mention the first World War. I’d written about his war record in two poetry collections, but now I wanted to explore his fictional potential for a piece of crime fiction, and so honed in on his experiences as a policeman in newly independent Ireland.

Grandad left the National Army in 1924 and, like many other ex-soldiers, joined the nascent Garda Síochána. To get further background on that part of his career, I contacted the Garda Archive in Dublin Castle to ask if they had a record of him. By return of email came an A4 document that provided the bare minimum: his badge number, date of birth, date of appointment (March 28th, 1925), the stations and divisions where he served, monetary awards received (for good police duty) and date of discharge (March 29th, 1945).

The final entry related to his total service (some 20 years and two days), and the statement “Exemplary Service”. Never have two words been more frustrating; I wanted to hear the details of that service, the cases he’d investigated, the turmoil he’d witnessed in the early years of the new Free State. But if those records were still held anywhere, I wasn’t getting access to them.

There’s nothing a writer likes more than a vacuum, because that’s what frees up the imagination and allows us to invent. I became convinced that if officialdom couldn’t give me the facts, some imagination backed up by historical research might help fill in the gaps. The more I read, the more it became clear that the new police force Michael McCann joined had been thrown into the deep end of an Irish society still deeply divided and lawless. What a perfect scenario for the fictional hero I was beginning to envisage.

Given the breadth of those divisions, the nature of the force tasked with guarding the peace was hugely important. In 1922, Gen Eoin O’Duffy and Kevin O’Higgins planned to establish a Civic Guard, or Garda Síochána, to replace the Royal Irish Constabulary. This force was to be unarmed and politically neutral, though answerable to the Government Minister responsible for their administration. By the end of 1924 and the beginning of 1925, with the Army scaling back (some 30,000 soldiers were made redundant and few had jobs to go back to), it was clear that this new unarmed police force might need strengthened resources.

As Conor Brady puts it in Guardians of the Peace, his history of the Garda Síochána, “some districts remained peaceful after the military had been withdrawn … huge areas of Cork, Kerry, Tipperary, Clare and the Border country immediately became open territory not only for the remaining active bands of Republicans who could find very good reason to rob banks on behalf of the Republic but also groups of ordinary armed bandits. There was, furthermore, a mushrooming problem of disbanded Free State troops turning to violent crime.”

O’Higgins and O’Duffy decided that a restructuring would be required to provide the sort of policing needed in a still highly unstable situation. So in 1925, the Garda Síochána and the Dublin Metropolitan Police were amalgamated and, as part of this newly unified body, a new entity was created, the ‘Special Branch’. The leader of this new outfit was to be David Neligan, one of Michael Collins’s original secret service agents and now a colonel in the Free State Army.

O’Higgins stipulated that members of the new armed detective team should be recruited from the Civic Guards and from the Free State Army Office corps. There were to be about 200 men in this new unit, divided between Dublin and 20 Garda divisions around the country. They were to be given six months of training in areas such as criminal law, police procedure, ballistic and forensic evidence and the use of firearms and self-defense.

My grandfather was appointed as a member of the Garda Síochána and joined the Special Branch on its formation shortly afterwards. He was stationed first in Letterkenny, before being moved to Ballinasloe in 1929, where he spent the majority of his career.

Although the Civil War had been over for several years, the Galway region was still pretty unsettled when my grandfather was transferred there. Ammunition left over from the conflict could cause security problems. On March 1st, 1930, there was a major blast at the back of Society Street in Ballinasloe, which led to the demolition of some shop fronts and the destruction of the offices of the local newspaper, The East Galway Democrat. As The Irish Times reported, “investigations were made by the Civic Guards, and it is thought that a land mine, which was probably hidden by someone who wanted to get rid of it in an ash pit or somewhere behind Society Street, was accidentally exploded”. Later that year, an Irish Omnibus Company vehicle travelling from Galway to Athlone was fired upon from a field on the Athenry to Ballinasloe road. And in September 1931, the Civic Guard barrack at nearby Kilreekil was blown up.

The more I read, the more it became clear that the new police force Michael McCann joined had been thrown into the deep end of an Irish society still deeply divided and lawless. Trouble never seemed too far away in Ballinasloe in those days. In April 1935, The Irish Times reported that that three shots had been fired into the house of Michael Killeen, Brackernagh. Mrs Killeen, who had been sitting near the sitting-room window, narrowly avoided injury. At a military tribunal the following month, John Keogh of Deerpark, Ballinalsoe, was tried and sentenced to two years in prison for the attack on Killeen, who had been secretary of the Poolboy and Kellysgrove Peat Development Association. In 1941, my grandfather gave evidence in a court case involving a husband and wife in whose house guards had discovered a cache of ammunition and bank notes. According to press reports, Michael had been part of a group searching the house and had discovered the cache “in a groove cut out of the leg of the table”.

My uncle, Liam McCann, (now deceased) also remembered an event from the early 1930s. There had been a hurling match in Duggan Park in Ballinasloe. It got out of hand and my grandfather arrested a man and brought him down to the barracks. A mob came down to try and storm the barracks and Granddad had to fire a gun over their heads to disperse the crowd.

So there was no shortage of incidents that could fuel the fiction I was planning to write. My novel, titled The Branchman and published this month by Arlen House, incorporates some of them and invents many others. It features a newly appointed Special Branch Detective called Michael Mackey, assigned to the Ballinasloe police barracks with the task of discovering the subversives at work there. Of course he bears more than a passing resemblance to my grandfather but, as with many fictional heroes, has his own characteristics, flaws and plot points, which almost certainly never happened in real life, or at least not in the way I tell them here. But that is the joy of historical fiction; it presents an alternative reality. If the writer can make the reader believe in that reality, at least from the first page to the last, she has succeeded in her task.

As this decade of commemoration advances, more and more stories are being unearthed about the unstable society that the new Free State attempted to pacify in the aftermath of Civil War. It’s a rich subject for fiction; I look forward to reading the many imaginative responses that will undoubtedly follow.

A version of this article first appeared in the Irish Times on 19th September 2018.

Copies of The Branchman now on Pre-order

Delighted to say that copies of The Branchman can now be pre-ordered on Book Depository at

https://www.bookdepository.com/Branchman-Nessa-OMahony/9781851321896?ref=grid-view&qid=1536127623818&sr=1-3

A novel new experience

Although I've focussed on poetry throughout my writing career, I've always been an avid reader of fiction, and much of my poetry has tended towards the narrative. So it was only a matter of time before I ventured into the brave new world of fiction writing. That I should want to write crime came as no surprise to me; my earliest reading as a young teenager was the novels of Agatha Christie; I worked my way through P.D. James, Ruth Rendell and though I never read Colin Dexter's novels, I became addicted to the TV adaptation of his Chief Inspector Morse (and the sequels and prequels that followed).

I've always believed that we should write what we enjoy reading, so in 2015 I took my courage in my

hands and signed up for a course in crime fiction with Irish thriller-writer, Louise Phillips. In an incredibly instructive 10 weeks, Louise took us through the intricacies of structure, suspense, hooks and dialogue. Her first piece of advice was the most crucial; she pointed out that if you wrote 500 words a day, you'd have a full-length novel within the year. She encouraged us to email her our weekly word count, and even provided a handy grid so that we could fill out our daily rate. I got up at 5.30am and wrote until 7am every morning that course ran, and had the best part of 20,000 words written before it had ended. It took me another two years to complete the remaining 60,000 and another year again to edit, refine, edit again to the point that I was ready to send it out.

So i was thrilled when Irish publisher Alan Hayes of Arlen House said he'd like to publish the book, The Branchman, which is soon to make its first appearance in the world.

So what's it about? It's about a Special Branch Detective, Michael Mackey, who is sent to a small East Galway town to uncover a nest of subversives and a possible traitor within the police station to which he has been assigned. It's about the utterly lawless world of post Civil War Ireland, where nearly everyone had a gun, or a secret, or both. It's about murder and love and jealousy.

I enjoyed writing it enormously, wanting above anything else to create a story that people would want to finish, pages they'd want to turn and characters they'd come to care about. I hope you enjoy The Branchman. There's more where that came from.

The Branchman will be launched by novelist Catherine Dunne at 6.30pm on Tuesday 18th September, alongside new work by Mary O'Donnell and Sophia Hillan, at the Irish Writers Centre, Parnell Square, Dublin 1.