Guest post by poet Colin Dardis on poetry and mental health

To coincide with the launch of his latest poetry collection, 'The Dogs of Humanity', I'm hosting poet Colin Dardis, who discusses here the overlaps between poetry and mental health in his work:

“I have not been named,

so they never talk of me. I call myself runt,

a title earnt through exclusion.”

(‘Runt’)

I’m twelve, and sitting in my doctor’s GP clinic, waiting to be seen by a nurse for an appointment. The reason why I am here exactly have been lost through the distance of time. However, a new reason for future appointments will soon appear.

I’m on a cushioned bench, on my own, outside the nurse’s office. The colours are all pastel blue and light grey, simple neutral tones you’ll find in any surgery. Suddenly, I’m overwhelmed by a pounding headache, a sense of dizziness… I feel like monsters are rushing at my from off the walls, creatures I can’t really see but it feels like a video game where you can’t shoot fast enough. I close my eyes and lower my head. The sensation lasts a minute and then passes. I don’t know what to make of it, and do not mention it to anyone.

Years later, I came to realise that this was my first panic attack. And since then, I’ve been struggling with depression and anxiety all throughout my adolescence and adult life.

“How many are scared tonight?

How many want to burrow into the nest

like the newly-hatched cuckoo

and cry the loudest in order to fed…”

(‘The Humane Animal’)

Of course, I didn’t realise this at the time. In my teens, I didn’t identify as someone with depression, didn’t seek a diagnosis, or given any medication or therapy. Twenty years ago, there just wasn’t the awareness we have now of these issues. So instead of talking openly about these issues, knowing I was somehow different from ‘the norm’, everything went into poetry instead.

Writing allows a realm in which to explore and try to understand the things that didn’t make sense in everyday life. How do people relate to each other? How is one supposed to behave? What am I expected to do with my feelings? Life rarely gave answers to these questions, but in poetry, you could create your own makeshift answers. Or at least, the question seems less daunting than before.

A lot of poetry in the past has been introspective, as mental health was my main impetus to write. However, as I’m grown older (not necessarily matured!), and grown more comfortable in sharing my experiences, I’ve realised that more and more people are experiencing something similar to me. That at times they have felt lost, unsure of the future, burdened with a grief they can’t quite explain. And so my poetry has moved to try and look at that bigger question of the human condition, to advocate for more empathy from people, to dig into a place of resilience. In a society where we say “it’s okay not to be okay”, there are still so many people unable to speak up. Poetry, whether in the act of writing or reading it, gives us the opportunity to find those words unsaid, to perhaps find a little comfort through words, which ultimately, can lead to actions.

“Life would not reach print

by the high demands

of us human publishers,

yet it is the only manual

we have to read.”

(‘Unpublished’)

Colin’s new collection, ‘The Dogs of Humanity’, is out 1st August, available to pre-order now from Fly On The Wall Press:

Print: https://www.flyonthewallpoetry.co.uk/product-page/pre-order-the-dogs-of-humanity-by-colin-dardis

Kindle: https://www.amazon.co.uk/Dogs-Humanity-Chapbook-Colin-Dardis-ebook/dp/B07TCBCZ64/ref=sr_1_3

Discussing the creative response to historical events in early 20th century Ireland

I recently gave a paper at the inaugural Association of Writing Programmes Ireland conference at University College Dublin about the challenges of writing historical fiction - I was part of a panel with novelist Mary O'Donnell, who discussed the writing of her recent short fiction collection, Empire (Arlen House 2018). There was some fascinating discussion afterwards so I'm posting my paper here:

FINDING THE FICTIVE SPACE WITHIN CONTESTED FACT

As our abstract has suggested, the current Decade of Commemoration has brought into the open many stories previously hidden from the narrative mainstream of received history. In my presentation I am focussing on the creative response to the convulsive events of the first quarter of the 20th century, namely World War I, the Rising and War of Independence and Civil War, using my own experiences as a creative writer as the main basis of discussion, and seeking to place that practice in the tradition of how others have responded imaginatively to the period.

In this presentation, I’ll consider the issues around the creative response to factual events in the first quarter of the 20th century, before focussing on my own experience of writing the first novel in a trilogy exploring the experiences of an ex-army turned policeman in the Irish Free State. When I began this paper, I had a fairly clear outline of what I intended to cover. But that was before the events in Derry last week when journalist and writer Lyra McKee was shot dead during rioting in the Creggan, when a paramilitary took aim at police and killed her instead. That event reminded me that politically-inspired violence in Ireland is not confined to history, and that writers continue to have to grapple with the legacy of our confused and contested past. I’ll return to that point at the end of this paper.

Understanding the past is crucial, and when you begin to write historical fiction, you quickly realise the limits to your knowledge of history. I was speaking to another writer recently about how we were taught the subject. She, a generation ahead of me, mentioned that secondary school history had stopped at the Tudors. In a brief addendum, the 1916 Rising was mentioned as having taken place, but no future details were provided. This was in the 1960s, when the events at the GPO and elsewhere were not even half a century old. I studied history at school in the 1970s, and took it as a subject at university here in Belfield in the early 80s. By that stage, there were plenty of accounts of the Easter Rising, and whole text books consisted of a chronology of rebellions from the Flight of the Earls to Soloheadbeg, that suggested the only possible relationship between Ireland and England was a dysfunctional one, with uprisings the inevitable and sole solution. This kind of history focussed on the minority of men and women involved in the planning of those uprisings; little account was taken of the majority of the population whose lives were of course affected by political events but who went on with their day to day routines as best they could – the one exception were the lectures of Mary Daly, who crucially conveyed the social history in an admirably compelling way. But, by and large, the stories of everyday men and women of the period remained untold.

By the historians, that is.

Writers were a different matter, and although literature of the political unrest was not numerous during the early decades of the 20th century, there were notable exceptions. Yeats, of course, gave us his own idiosyncratic take on violent nationalism. Sean O’Casey’s plays represented ordinary men and women caught up in extraordinary events. Juno and the Paycock tackled the harsh brutalities of life during the Civil War – his Shadow of a Gunman attracted enormous contemporary criticism for its unvarnished depiction of both revolutionaries and Dubliners. Liam O’Flaherty’s The Informer, published in 1925, won the James Tait Black Memoiral Prize that year for his depiction of Gypo Nolan, the eponymous informer who goes on the run in the Civil War. In 1929, Elizabeth Bowen published The Last September, which told the story of the Anglo-Irish family The Naylors against a backdrop of the War of Independence. In 1931, Frank O’Connor published his short story “Guests of the Nation,” in a collection of the same name. For many years this was considered the seminal story of the War of Independence, telling as it did the story of two British soldiers shot dead by the Irish Volunteers during the War of Independence. It was certainly the only story dealing with the period that was on the curriculum when I was at school.

But in the 30s, it seemed to go silent. Scholars will have their theories about why the period between 1930 and 1970 did not produce more writing about the bloody events that had given birth to the Irish Free State and then Republic. De Valera’s Ireland did not encourage much self-reflection or social scrutiny so writers may have preferred to cast their nets elsewhere – one thinks of the surreal satire of Flann O’Brien, or the medieval monastic whimsy of Mervyn Wall’s Unfortunate Fursey.

It’s certainly possible that the Censorship Board, established in 1929, might also have had something to do with. Although its remit was the safeguarding of ‘public morality’ through the banning of obscene literature, it soon became clear that the Censor took a very broad view of what constituted ‘obscene’ and soon was banning anything that might challenge a very narrow public consensus. In such a climate, it was hardly likely that Irish writers would seek to challenge political orthodoxies.

And so it remained until the mid-60s, when the social climate began to change and slowly, gradually, people began to challenge nationalist pieties in a way that would have been unthinkable previously. The historians may have started writers rethinking their approach – when I studied history here at UCD in the early 1980s, revisionism was only beginning to make itself felt, and early work by Ruth Dudley Edwards, amongst others, began to suggest that we might find other ways of looking at long-held truths, though that was not the consensus view by any means. Creative writers may have been emboldened by that revision.

But it was an uncomfortable time to be doing so. The Northern Ireland Troubles were under way, and from my very youthful perspective at the time, it felt like there were divided loyalties in the Republic. We still liked to cheer whenever the British got beaten in any sport, but, depending on your viewpoint, honouring our Fenian Dead could be seen as acknowledging a link between them and the current breed of paramilitaries responsible for such carnage on both islands. How to reconcile that sort of cultural ambivalence, and how to write about it creatively?

I don’t have the scope in this paper to discuss the literature of the Northern Irish Troubles. Given that my own creative focus has been on the first quarter of the 20th century, since I began to explore in fiction the lives of the men and women caught up in the various conflicts of that period, that’s what I want to discuss now.

Julian Gough once courted controversy by stating that Irish novelists were obsessed with the past. Writing in his blog in 2010, he said: The older, more sophisticated Irish writers that want to be Nabokov give me the yellow squirts and a scaldy hole. If there is a movement in Ireland, it is backwards. Novel after novel set in the nineteen seventies, sixties, fifties. Reading award-winning Irish literary fiction, you wouldn't know television had been invented. Indeed, they seem apologetic about acknowledging electricity.” (https://www.theguardian.com/books/2010/feb/11/julian-gough-irish-novlists-priestly-caste accessed 18/4/19)

Gough rowed back on his comments a little later, but it’s interesting to consider, even in his commentary, the lack of focus on the earlier part of the 20th century. Where were the contemporary novelists who were writing about that period (Apart from Jennifer Johnston’s How Many Miles to Babylon, published in 1974 and still one of the finest Irish novels about the Great War)?

The decade of commemoration acted as a galvanising force, it would seem. Two things were going on here. Firstly, the more the public discourse turned to considering and reconsidering the events of 100 years ago, the more writers began to explore that world imaginatively. Secondly, I’m sure there was a commercial imperative. Publishers are quick to see the attractions of anniversary-themed books (think how many books came out this year around the theme of female suffrage and forgotten women) so they may have been more open to proposals around historic themes. It can be no coincidence that over the past two decades we’ve seen books by Roddy Doyle (His The Last Roundup Trilogy which began with A Star Called Henry, 1999), Lia Mills (Fallen), Sebastian Barry (A Long, Long Way), Mary Morrissy (The Rising of Bella Casey) and, in the crime/thriller field, series by Kevin McCarthy and Joe Joyce among others. Nicola Pierce and Sheena Wilkinson have been exploring the period for children and young adult fiction.

For me as a poet and novelist, it seemed inevitable that I would be drawn to the period. I grew up hearing about the adventures of men and women in that period of time. My mother is a terrific storyteller and my childhood was filled with accounts of my grandfather’s exploits in the War of Independence, and the Civil War. When I began to write, I quickly found that family history was an important subject matter for me. But there were gaps in my knowledge. Family history is never complete, particularly when reticence is part of the mix.

It was only when I began, five years ago, to professionally research the life of my grandfather, Michael McCann, that I discovered that there was considerably more to him than family history had told. Not surprisingly, those family stories had centred on his role as a Volunteer during the War of Independence, though details were sketchy even there, and as a Commandant in the Free State Army during the Civil War. There was practically no mention of the fact that he’d fought on the Somme in World War I – that part of his backstory had been carefully elided. But as we approached the centenary of the start of the First World War, I was anxious to fill in the gaps and, with the help of my surviving uncle, Liam McCann, who was in possession of Granddad’s soldier’s pocketbook, which gave his medal number, I was able to track down a fuller account of his involvement. He enlisted in 1915, joined the Royal Munster Fusiliers, and spent 1916 and part of 1917 on the Western Front, in particular the Somme. He was injured by shrapnel, and invalided out in late 1917. It was then that he moved to North East England, and joined a faction of the Irish Volunteers.

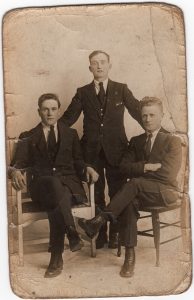

I had written about his Civil War activities in my second poetry collection (Trapping a Ghost, bluechrome 2005), but I’d never written about his First World War activities. Now, with the additional information I’d gained through research, I was able to write a series of poems that charted his progress through the war, and the legacy of injury it had left. Those poems appeared in my 2014 collection, Her Father’s Daughter; I used as the cover photo a snap of my grandfather in his Royal Munster Fusilier’s uniform. I’d not been aware of the photograph’s existence, nor had my mother, but was sent it by a second cousin I uncovered during online research into my grandfather’s family. On the night of the launch, I discovered that choice was not entirely uncontroversial. At the end of the evening, an aunt approached me, wondering why I hadn’t, instead, used one of the many photographs of Granddad in his Free State Army uniform. The family was not universally ready to accept the many-faceted nature of my grandfather’s history, it would seem.

And yet, that was precisely the point of writing those poems, and making use of that photo. My grandfather had not spoken at all about his First World War record, in common with the thousands of Irishmen and women who’d survived that bloody conflict, and who had come home to an Ireland ‘changed utterly’ and utterly unreceptive to their plight. If they did talk about it, they could be a target for political nationalists. So the safest thing to do was to stay quiet. I was convinced of the need to to reinstitute at least one of those voices, to claim that covert experience fighting for Britain as every bit as valid and worthy of writing about as the more politically acceptable activities that followed it.

The choice of my next book, a crime novel inspired by my grandfather’s 20-year career in An Garda Siochána, seemed a less controversial choice. There was more family anecdotal evidence to draw upon, as my mother and her siblings were around for most of it, but there were still gaps in their knowledge, stories half-remembered or conflated. And when I approached the Garda Archive in Dublin Castle to see if they had further information, they sent by return of email an A4 document that provided the bare minimum: his badge number, date of birth, date of appointment (28 March 1925), the stations and divisions where he served, monetary awards received (for good police duty) and date of discharge (29 March 1945). Oh, and the final entry, was a description of his total service as ‘Exemplary’. That could have covered a multitude.

As you know, there’s nothing a writer likes more than a vacuum, because that’s what frees up the imagination and allows us to invent. I became convinced that if officialdom couldn’t give me the facts, some imagination backed up by historical research might help fill in the gaps. The more I read of the background, from local newspaper reports and historical accounts, the more it became clear that the new police force Michael McCann joined had been thrown into the deep-end of an Irish society still deeply divided and lawless after the ending of the Civil War. It was a society I was deeply curious about, but one that I had rarely if ever read about. Thus it was one I wanted explore in fiction.

The background to the Special Branch that my Grandfather joined, and which is the subject of my novel, The Branchman, is as follows. In the period immediately after the end of the Civil War, Minister for Home Affairs Kevin O’Higgins and Garda Commissioner Eoin O’Duffy decided that a restructuring of the police force would be required to provide the sort of policing needed in a still highly unstable situation. So in 1925, the Garda Síochána and the Dublin Metropolitan Police were amalgamated and, as part of this newly unified body, a new entity was created, the ‘Special Branch’. The leader of this new outfit was to be David Neligan, one of Michael Collins’s original secret service agents and now a Colonel in the Free State Army.

My grandfather, Michael McCann, was appointed as a member of the Garda Síochána of 28th March, 1925, and joined the Special Branch on its formation shortly afterwards. He was stationed first in Letterkenny, before being moved to Ballinasloe in 1929, where he spent the majority of his career.

My fictional hero, Michael Mackey, was also appointed to the Special Branch in 1925, although he went straight to Ballinasloe to conduct his investigations into suspected subversives in the area. Although the plot is highly fictionalized, I did draw on actual events. For example, I’d read an article in the Irish Times archives that cached ammunition left over from the Civil War regularly caused security problems in small Irish towns. For example, 1st March, 1930, there was a major blast at the back of Society Street in Ballinasloe, which led to the demolition of some shop fronts and the destruction of the offices of the local newspaper, The East Galway Democrat. As The Irish Times reported, “investigations were made by the Civic Guards, and it is thought that a land mine, which was probably hidden by someone who wanted to get rid of it in an ash pit or somewhere behind Society Street, was accidentally exploded”. I took the kernel of this event for the novel, and an early incident involves Mackey discovering a cache of weapons in the murder victim’s coal shed, and engaging in a shoot-out with one of the subversives.

Another plot twist inspired by actual events came courtesy of my uncle, Liam McCann (now dead), who also remembered an event from the early 1930s. There had been a hurling match in Duggan Park in Ballinasloe. It got out of hand and my grandfather arrested a man and brought him down to the barracks. A mob came down to try and storm the barracks and Granddad had to fire a gun over their heads to disperse the crowd. In the novel, this gets translated into a major grudge match between two arch rival teams in a county final that occurs on the same day as a visit to Ballinasloe by Minister Kevin O’Higgins. The fans have been infiltrated by subversives who incite a riot that spills out into the official visit, with fatal consequences.

By the way, I am only too aware that my choice of terminology – of subversives and Irregulars – might seem to nail my political allegiances to the mast. The Free State authorities coined the phrase ‘Irregular’ for those men who were against the Treaty and formed their own military opposition to it. Those who grew up in that Anti-Treaty tradition would more likely refer to them as Volunteers, or Republicans, phrases that are as loaded today as they were then – the initial statement commenting on Lyra McKee’s death was attributed to Volunteers. But although my protagonist Michael Mackey might be in no doubt about who the ‘baddies’ were in 1925, the reader will gradually discover that things in the new Free State are not quite that black and white. People on all sides of the divide are forced to compromise morals and integrity on a regular basis; my choice of the crime genre provided me with a useful framework for such an exploration. Crime readers are used to depictions of corrupt societies where nobody is beyond suspicion; my use of a small Irish town as a microcosm for larger dark forces at play in a riven Irish society would not shock anybody familiar with those tropes. Indeed, a recent review of the book by novelist Pauline Hall recognized those similarities:

"The originality of this novel lies in O’Mahony’s treating of dirty work in Co Galway in 1925 within many of the conventions of American private eye fiction. I suspect that Nessa is, like myself, a fan of the peerless Raymond Chandler. Her hero, Michael Mackey – the Branchman – has to go down mean streets, without being mean himself. Like Philip Marlowe, he can exchange blows and shots when required, but he resembles Marlowe also in his stubborn principles and his romantic attachment to a tough broad."

But does writing in a recognizable tradition such as the crime thriller allow one license to mix fact and fiction in such a way? I would argue yes, although I’m aware that more than one reader (with connections to the town) has complained about the depiction of Ballinasloe people in the novel, although others had no such problem. I’d claim that novelists must engage with the past through their own imaginative filter. My protagonist bears more than a passing resemblance to my grandfather but, as with many fictional heroes, has his own characteristics, flaws and plot points, which almost certainly never happened in real life, or at least not in the way I tell them in the novel. But isn’t that is the joy of historical fiction; it presents an alternative reality. If the writer can make the reader believe in that reality, at least from the first page to the last, she has succeeded in her task.

Or so I thought before the events of last week in Derry City. Now I wonder whether writers have a duty to the past, to recognize that what might be considered finished business in some eyes is still very much alive and current and thus must be handled with greater care and attention. Might that explain the silence that descended upon Irish writers in the decades after the cessation of the Civil War, a reluctance to deal with what was very much still a source of live debate and dissention? Was it the ending of the Northern Irish Troubles in 1997 that freed up creative writers to tackle these subjects again? And will the arrival onto the scene of a new generation of paramilitaries still trying, in the words of Paul Brady, to ‘carve tomorrow from a tombstone?’ make us more hesitant to write about those events of 100 years ago?

I don’t have any answers to this. I know that as this decade of commemoration advances, more and more stories will be unearthed about the unstable society that the new Free State attempted to pacify in the aftermath of Civil War. It remains a rich subject for fiction; I hope I hold my courage to continue that imaginative exploration.

Thank you

The man behind the Branchman - Michael McCann

Five years ago I began to research the life of my grandfather, Michael McCann, a man who has haunted much of my creative writing since I first heard my mother’s stories about his exploits during the War of Independence and Civil War, not to mention the first World War. I’d written about his war record in two poetry collections, but now I wanted to explore his fictional potential for a piece of crime fiction, and so honed in on his experiences as a policeman in newly independent Ireland.

Grandad left the National Army in 1924 and, like many other ex-soldiers, joined the nascent Garda Síochána. To get further background on that part of his career, I contacted the Garda Archive in Dublin Castle to ask if they had a record of him. By return of email came an A4 document that provided the bare minimum: his badge number, date of birth, date of appointment (March 28th, 1925), the stations and divisions where he served, monetary awards received (for good police duty) and date of discharge (March 29th, 1945).

The final entry related to his total service (some 20 years and two days), and the statement “Exemplary Service”. Never have two words been more frustrating; I wanted to hear the details of that service, the cases he’d investigated, the turmoil he’d witnessed in the early years of the new Free State. But if those records were still held anywhere, I wasn’t getting access to them.

There’s nothing a writer likes more than a vacuum, because that’s what frees up the imagination and allows us to invent. I became convinced that if officialdom couldn’t give me the facts, some imagination backed up by historical research might help fill in the gaps. The more I read, the more it became clear that the new police force Michael McCann joined had been thrown into the deep end of an Irish society still deeply divided and lawless. What a perfect scenario for the fictional hero I was beginning to envisage.

Given the breadth of those divisions, the nature of the force tasked with guarding the peace was hugely important. In 1922, Gen Eoin O’Duffy and Kevin O’Higgins planned to establish a Civic Guard, or Garda Síochána, to replace the Royal Irish Constabulary. This force was to be unarmed and politically neutral, though answerable to the Government Minister responsible for their administration. By the end of 1924 and the beginning of 1925, with the Army scaling back (some 30,000 soldiers were made redundant and few had jobs to go back to), it was clear that this new unarmed police force might need strengthened resources.

As Conor Brady puts it in Guardians of the Peace, his history of the Garda Síochána, “some districts remained peaceful after the military had been withdrawn … huge areas of Cork, Kerry, Tipperary, Clare and the Border country immediately became open territory not only for the remaining active bands of Republicans who could find very good reason to rob banks on behalf of the Republic but also groups of ordinary armed bandits. There was, furthermore, a mushrooming problem of disbanded Free State troops turning to violent crime.”

O’Higgins and O’Duffy decided that a restructuring would be required to provide the sort of policing needed in a still highly unstable situation. So in 1925, the Garda Síochána and the Dublin Metropolitan Police were amalgamated and, as part of this newly unified body, a new entity was created, the ‘Special Branch’. The leader of this new outfit was to be David Neligan, one of Michael Collins’s original secret service agents and now a colonel in the Free State Army.

O’Higgins stipulated that members of the new armed detective team should be recruited from the Civic Guards and from the Free State Army Office corps. There were to be about 200 men in this new unit, divided between Dublin and 20 Garda divisions around the country. They were to be given six months of training in areas such as criminal law, police procedure, ballistic and forensic evidence and the use of firearms and self-defense.

My grandfather was appointed as a member of the Garda Síochána and joined the Special Branch on its formation shortly afterwards. He was stationed first in Letterkenny, before being moved to Ballinasloe in 1929, where he spent the majority of his career.

Although the Civil War had been over for several years, the Galway region was still pretty unsettled when my grandfather was transferred there. Ammunition left over from the conflict could cause security problems. On March 1st, 1930, there was a major blast at the back of Society Street in Ballinasloe, which led to the demolition of some shop fronts and the destruction of the offices of the local newspaper, The East Galway Democrat. As The Irish Times reported, “investigations were made by the Civic Guards, and it is thought that a land mine, which was probably hidden by someone who wanted to get rid of it in an ash pit or somewhere behind Society Street, was accidentally exploded”. Later that year, an Irish Omnibus Company vehicle travelling from Galway to Athlone was fired upon from a field on the Athenry to Ballinasloe road. And in September 1931, the Civic Guard barrack at nearby Kilreekil was blown up.

The more I read, the more it became clear that the new police force Michael McCann joined had been thrown into the deep end of an Irish society still deeply divided and lawless. Trouble never seemed too far away in Ballinasloe in those days. In April 1935, The Irish Times reported that that three shots had been fired into the house of Michael Killeen, Brackernagh. Mrs Killeen, who had been sitting near the sitting-room window, narrowly avoided injury. At a military tribunal the following month, John Keogh of Deerpark, Ballinalsoe, was tried and sentenced to two years in prison for the attack on Killeen, who had been secretary of the Poolboy and Kellysgrove Peat Development Association. In 1941, my grandfather gave evidence in a court case involving a husband and wife in whose house guards had discovered a cache of ammunition and bank notes. According to press reports, Michael had been part of a group searching the house and had discovered the cache “in a groove cut out of the leg of the table”.

My uncle, Liam McCann, (now deceased) also remembered an event from the early 1930s. There had been a hurling match in Duggan Park in Ballinasloe. It got out of hand and my grandfather arrested a man and brought him down to the barracks. A mob came down to try and storm the barracks and Granddad had to fire a gun over their heads to disperse the crowd.

So there was no shortage of incidents that could fuel the fiction I was planning to write. My novel, titled The Branchman and published this month by Arlen House, incorporates some of them and invents many others. It features a newly appointed Special Branch Detective called Michael Mackey, assigned to the Ballinasloe police barracks with the task of discovering the subversives at work there. Of course he bears more than a passing resemblance to my grandfather but, as with many fictional heroes, has his own characteristics, flaws and plot points, which almost certainly never happened in real life, or at least not in the way I tell them here. But that is the joy of historical fiction; it presents an alternative reality. If the writer can make the reader believe in that reality, at least from the first page to the last, she has succeeded in her task.

As this decade of commemoration advances, more and more stories are being unearthed about the unstable society that the new Free State attempted to pacify in the aftermath of Civil War. It’s a rich subject for fiction; I look forward to reading the many imaginative responses that will undoubtedly follow.

A version of this article first appeared in the Irish Times on 19th September 2018.

A novel new experience

Although I've focussed on poetry throughout my writing career, I've always been an avid reader of fiction, and much of my poetry has tended towards the narrative. So it was only a matter of time before I ventured into the brave new world of fiction writing. That I should want to write crime came as no surprise to me; my earliest reading as a young teenager was the novels of Agatha Christie; I worked my way through P.D. James, Ruth Rendell and though I never read Colin Dexter's novels, I became addicted to the TV adaptation of his Chief Inspector Morse (and the sequels and prequels that followed).

I've always believed that we should write what we enjoy reading, so in 2015 I took my courage in my

hands and signed up for a course in crime fiction with Irish thriller-writer, Louise Phillips. In an incredibly instructive 10 weeks, Louise took us through the intricacies of structure, suspense, hooks and dialogue. Her first piece of advice was the most crucial; she pointed out that if you wrote 500 words a day, you'd have a full-length novel within the year. She encouraged us to email her our weekly word count, and even provided a handy grid so that we could fill out our daily rate. I got up at 5.30am and wrote until 7am every morning that course ran, and had the best part of 20,000 words written before it had ended. It took me another two years to complete the remaining 60,000 and another year again to edit, refine, edit again to the point that I was ready to send it out.

So i was thrilled when Irish publisher Alan Hayes of Arlen House said he'd like to publish the book, The Branchman, which is soon to make its first appearance in the world.

So what's it about? It's about a Special Branch Detective, Michael Mackey, who is sent to a small East Galway town to uncover a nest of subversives and a possible traitor within the police station to which he has been assigned. It's about the utterly lawless world of post Civil War Ireland, where nearly everyone had a gun, or a secret, or both. It's about murder and love and jealousy.

I enjoyed writing it enormously, wanting above anything else to create a story that people would want to finish, pages they'd want to turn and characters they'd come to care about. I hope you enjoy The Branchman. There's more where that came from.

The Branchman will be launched by novelist Catherine Dunne at 6.30pm on Tuesday 18th September, alongside new work by Mary O'Donnell and Sophia Hillan, at the Irish Writers Centre, Parnell Square, Dublin 1.

What we remember, what we choose to forget

On Easter Monday 24th April, 1916, a group of some 1,000 Irishmen and women came into Dublin and occupied a series of buildings around the city. Their aim was to overthrow the British Government in Ireland by military force and to proclaim an Irish Republic. Over the next seven days, over 450 people died, 2,000 were wounded and the centre of Dublin largely destroyed by shelling. 15 of the leaders of the uprising were executed; a 16th was executed later that summer.

On Easter Monday 24th April, 1916, a group of some 1,000 Irishmen and women came into Dublin and occupied a series of buildings around the city. Their aim was to overthrow the British Government in Ireland by military force and to proclaim an Irish Republic. Over the next seven days, over 450 people died, 2,000 were wounded and the centre of Dublin largely destroyed by shelling. 15 of the leaders of the uprising were executed; a 16th was executed later that summer.

On the same day in April 1916, the second Battalion of the Royal Munster Fusiliers was stationed in France, awaiting orders for the next big push that was to become the Battle of the Somme later that summer.

There’s no real information about how soon the news of events in Dublin filtered through to Irish troops serving in France, or what impact it might have had on their mood. There are few reports of mutinies in the weeks that followed the Easter Rising; indeed the first that Irish soldiers may have been aware of the changed sentiment at home that followed the mass executions and internment was during their next leave home. Writers such as Sebastian Barry (in novels such as A Long Long Way) have vividly evoked that change in sentiment, as men who’d left Ireland as heroes returned to a hostile and embittered response.

Included in their numbers was my grandfather, Michael McCann, who had enlisted in the British Army in November 1915 and who had transferred to France some time in April 2016. It’s probable that he had been put to work as part of the Pioneer Battalion of the Munsters, providing the hard labour that created roads, tracks, emplacements and dugouts in the Loos-Marzingarbe-Les Brébas area (source Fourteeneighten Research). But by July he had been involved in the action that became the Battle of the Somme, one of the Great War’s bloodiest conflicts.

Afterwards, hundreds if not thousands of returning Irish soldiers left the British Army and joined the ranks of the Irish Republican Army where they became active in a campaign against a Crown that they’d been defending only months before. My grandfather was one such; he discharged from the British Army in March 1918 (he’d been treated for shrapnel injuries in 1917) but joined the IRA in England in October 1917, possibly having first joined an organisation such as the Irish Self Determination League or the Irish Labour Party. By 1919 he was on active duty with the IRA, taking part in arson attacks and munitions raids; by 1921 he was arrested during an attempted raid on an explosives magazine in Middlesbrough, and sentenced to five years penal servitude in Parkhurst. The subsequent Treaty and amnesty led to his release and return to Ireland in early 1922, just in time for the Civil War where he fought as a Free State Army commandant.

The Civil War had its own share of atrocities, but here too we’ll never know how battle-hardened veterans like my grandfather reacted to them. He kept it bottled up; even his own children knew little of his exploits, other than those reported on by a frequently partisan press. My aunts and uncles described him as a ‘quiet man’ who kept his thoughts to himself. Fragments of his story came down from my grandmother; over the last few years I’ve tried to research to fill the gaps. My collections Trapping a Ghost and Her Father’s Daughter (Salmon Poetry 2014) include some of the poems that resulted.

It’s clear that my grandfather was typical of a whole generation of Irishmen who experienced utter horror and were unable to find an outlet for those experiences. Irish society had embraced another mythology; the narrative of Irish nationalism left no space for other Irishmen who also believed they were fighting for their country.

One of the best elements of this current decade of commemoration has been the re-emergence of their stories. Works like Lia Mills’s marvellous novel, Fallen (which will be the Belfast-Dublin Two Cities One Book choice from April) are exploring the reality of lives for the thousands of individuals and families whose lives were transformed for ever, both by violence at home, and violence on those distant green fields.

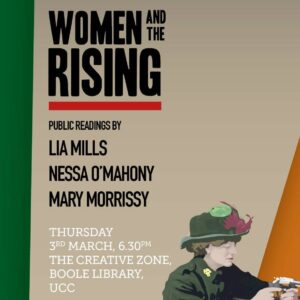

I’m incredibly lucky to be reading alongside Lia, and the marvellous Mary Morrissy, whose own novel The Rising of Bella Casey captured that tumultuous period of Irish history so well, as part of The Women and the Rising series at University College Cork on Thursday 3rd March. Further details on http://creativewritingucc.com/www/women-writers-remember-the-rising/.

I’ll also be leading a free creative writing workshop for the Open University on exploring family history at Castletown House in Celbridge, Co. Kildare, in late April. Details on how to book a place are on http://www.open.ac.uk/republic-of-ireland/events

Beat up little seagull - old tunes and new in Baltimore and DC

I've been lucky enough to work with some amazing writers and teachers over the past number of years. One of my happiest collaborations has been with the amazing faculty of the Armagh Project, a US-based outfit that brings undergraduate students over to Armagh for the month of July to experience the life, culture and politics of that extraordinary part of our island. Some of the faculty members of the Armagh Project are based at the University of Baltimore, in Maryland, and many of their students participate in the programme each year, so I was especially thrilled when UB-based playwright Kimberley Lynne invited me over to perform my work at the UB Spotlight's Charles Wright theatre during the month of April. Culture Ireland kindly agreed to support the trip, which also included a reading in Washington DC.

Kimberley also suggested that, while in Baltimore, I might like to meet some of the class groups to talk about Irish culture and poetry, so the reading tour took on a whole additional dimension as I cast about for subjects that would suit the different class groups, who study 20th century culture and ideas, creative writing and Irish studies. I felt rather privileged to get a chance to talk about my country, its writers and history, to groups of American students, and also rather daunted. I wanted to get the balance right - to be informative and accessible without being simplistic. In fact, many of these students turned out to be far more informed about Ireland and its history than I was, down to the expertise and dedication of teachers like Kimberley and Joan Weber, a writer and theatre in education specialist, who have immersed themselves in Irish culture over the years.

The reading at the Wright Theatre was great fun; the audience was attentive and informed and there was an excellent question and answer session at the end during which I was asked about my predilection for water-based imagery. It's marvellous when readers notice something one hadn't previously.

One of the best parts of visiting Baltimore was to get the chance to see it through the eyes of people who've lived their all their lives, or much of them. It is a beautiful city: a huge stretch of water (Chesapeake Bay) at its heart and extraordinary Victorian architecture at its centre. And I had wonderful tour guides. Both Kimberley and Joan are proud Baltimorians, and they taught me a great deal about its history, both distant and recent. The riots over the death in custody of Freddie Gray hadn't happened yet (in fact, they broke out just a day or two after we left the city) but he had already died and both Kimberley and Joan had been speaking about the tensions simmering in a city where the ethnic divide stretches back to the 'White Flight' of the post MLK assassination- troubles of 1968 and beyond to the legacies of the Civil War itself. Indeed Joan and I had been discussing the difficulties caused by the failure to face up to Civil War legacies, both in her country and on our small island. So it was very distressing to see reports of the trouble flaring up in the days after our departure. Baltimore is just the latest in a long line of similar events, with the same issues at their core. I just hope that some longer term solutions can be found, if Americans are prepared to do the sort of 'soul searching' that President Obama was recommending in the aftermath of Gray's death.

Throughout my visit, I referenced Randy Newman's song 'Baltimore', which I'd heard constantly growing up in a Churchtown house with a brother who was one of his greatest fans. Oddly enough, Newman's name rarely got more than a quizzical grunt when I mentioned him. Perhaps Baltimorians took his line 'It's hard to live' at face value; in a place where the cannon on the hill is aimed directly into the centre of the town (another Civil War legacy) they do tend to have a long memory.

Kind Words and Coronets

Like many writers with new books out there, I've been living in the suspended animation of anxiously awaiting the first book review to appear. While there have been many nice comments about the collection in person, via text, twitter, facebook direct messaging, there's nothing quite like the gravity of the printed word to concentrate the mind.

I'd love to claim a lofty disdain to all reviews, good and bad. But I've never been much of a liar - I lost my first book dedication in a poker game, after all. So I will admit that I cherish every nice thing said about my work, and promptly forget every single positive word uttered and written in the face of a negative notice. I'm not sure if that's human nature or simply my own neurosis at play, but it's a fact either way.

So I'm pleased to report that the first review in print appeared in the Irish Times on Saturday, and that poet and critic John McAuliffe had some nice things to say. You can read the full text of the review, which also discussed new books by Kerry Hardie, Theo Dorgan, Gerard Dawe and Jess Traynor, here.

But before you click the above link and disappear away from this blog, I thought I'd reproduce (with his permission) the stunningly kind introduction that the marvellous poet Damian Smyth gave to my work at the recent launch in No Alibis Bookstore in Belfast. It still stuns me that anyone would pay me so great a compliment as to notice what I've been up to, poetically. But Damian, as anyone who knows him will attest, is a very special kind of person. Anyway, here's what he says:

Blog Trotting

I'm going to be sharing this space with some fellow writers over the coming months as it's always interesting to see what other people are up to.

Uncovering a Hidden History

For much of my life, I had absolutely no idea that my grandfather, Michael McCann, had fought in the First World War. I grew up with the image of him as the archetypal Irish nationalist hero of the first decades of the twentieth century. A brooding photograph of him in Free State Army uniform and flat-topped army cap dominated the dresser in my mother’s kitchen; stories of his escapades in the War of Independence and the Civil War were an integral part of family lore. But there was no mention of the earlier conflict my grandfather was involved in, as a Lance Corporal for the Royal Munster Fusiliers. His experience, like that of so many of the hundreds of thousands of Irishmen who fought in World War I, had been quietly obliterated from the official narrative. There was no room in the nationalist mythology for any stories about those who fought for other causes.

Back to School Time 2014

It must be the chiller winds and browning leaves, not to mention the crab apples ripening on the tree outside my window, but thoughts turn to the new academic year, and the various courses I'll be teaching.

As I write, there are still some spaces available on the 10-week Finding the Story Course which I facilitate at the Irish Writers Centre in Parnell Square. It's a day-time course, running from 11am to 1pm and starting on Wednesday 24th September.